St Mary’s Seminary & University

Guide to Academic Writing

Mary Reisinger (Ecumenical Institute)

Bill Scalia (School of Theology)

Emily Hicks (School of Theology)

Introduction

St. Mary’s Seminary & University is a place of great diversity. The School of Theology prepares

seminarians from the United States and all over the world for priesthood. The Ecumenical

Institute provides advanced theological education for students from many branches of the

Church. Members of St. Mary’s student body have various academic, vocational, and cultural

backgrounds.

To help equip all students for the academic writing required in theological study, we have

prepared this brief guide to common types of writing tasks, general characteristics of effective

writing, and the Chicago Manual documentation of sources. Sample papers written by St.

Mary’s students appear in an appendix at the end of the booklet.

The advice in this document is intended to be generally useful. However, preferences vary

from one instructor to another. Students should carefully follow the requirements each

professor sets for assignments.

We wish all students an inspiring and rewarding experience as they embark on this journey of

discovery and transformation.

Acknowledgments

We have appreciated the substantial contributions many of our faculty colleagues have provided.

Whether you caught an error, suggested an addition or revision, endorsed a portion of the text,

or supplied a sample of student writing, we thank you. We are especially grateful for the support

and guidance of Dr. Michael J. Gorman, dean of the Ecumenical Institute; Dr. Pat Fosarelli,

Associate Dean of the Ecumenical Institute; Fr. Timothy Kulbicki, dean of the School of

Theology; Fr. Edward J. Griswald, Vice Rector of St. Mary’s Seminary & University; and Fr.

Thomas Hurst, President-Rector of St. Mary’s Seminary & University.

Finally, this guide has been shaped by our experience working with many St. Mary’s students.

Some of them have graciously allowed their papers to be included here as samples; we thank

them. We salute all our students, who teach us a great deal about writing instruction.

Table of Contents

Types of Academic Writing Used in Theological Study ................................................................. 1

Case Study ................................................................................................................................................ 1

Critique (sometimes called Review or Critical Response) ....................................................................... 1

Essay ........................................................................................................................................................ 1

Exegesis Paper.......................................................................................................................................... 2

Homily / Sermon ...................................................................................................................................... 2

In-Class Exam .......................................................................................................................................... 3

Journals .................................................................................................................................................... 3

Pastoral Narrative ..................................................................................................................................... 3

Précis (See Summary) .............................................................................................................................. 4

Reflection / Reflection Paper ................................................................................................................... 4

Research Paper ......................................................................................................................................... 4

Review (See Critique) .............................................................................................................................. 5

Sermon (See Homily / Sermon) ............................................................................................................... 5

Summary (sometimes called Précis) ........................................................................................................ 5

Verbatim ................................................................................................................................................... 5

Effective Academic Writing ............................................................................................................ 5

Unity ......................................................................................................................................................... 5

Support ..................................................................................................................................................... 5

Coherence ................................................................................................................................................. 5

Correctness ............................................................................................................................................... 6

Appropriate Style ..................................................................................................................................... 6

Scholarship ............................................................................................................................................... 6

Inclusive Language .......................................................................................................................... 7

General Guidelines for Research Writing ....................................................................................... 8

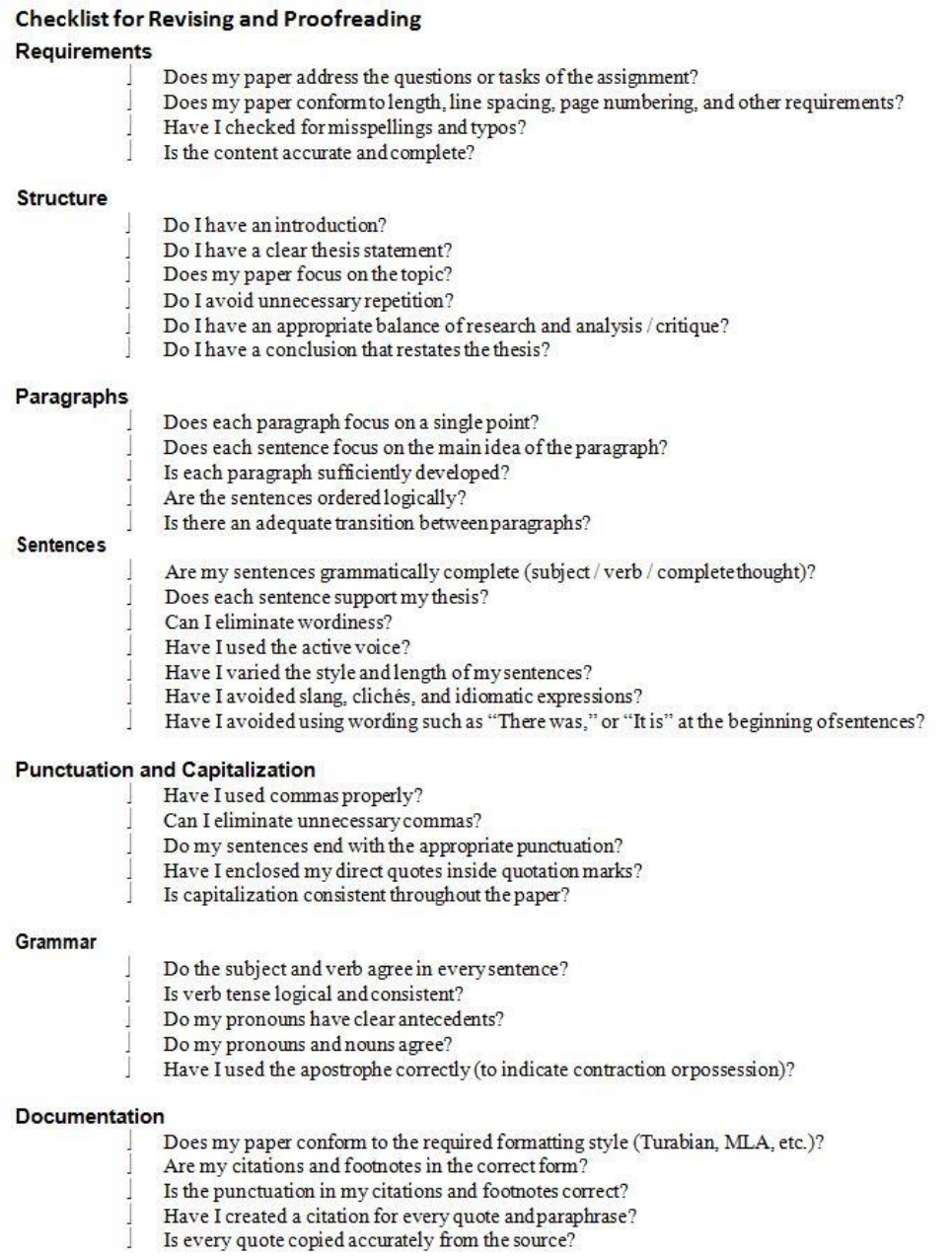

Checklist for Revising and Proofreading ......................................................................................... 8

Checklist for Revising and Proofreading ................................................................................................. 9

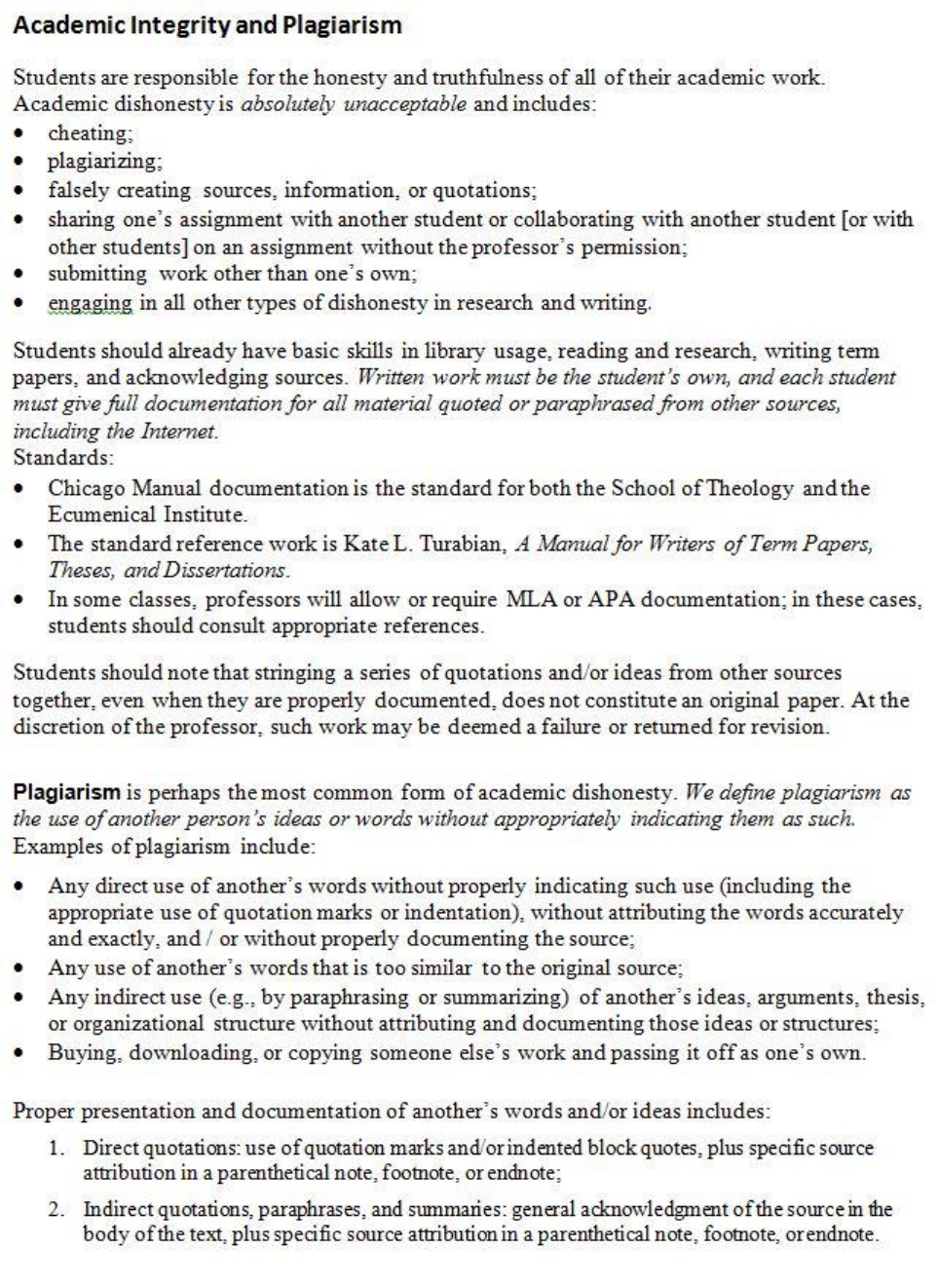

Academic Integrity and Plagiarism ............................................................................................... 10

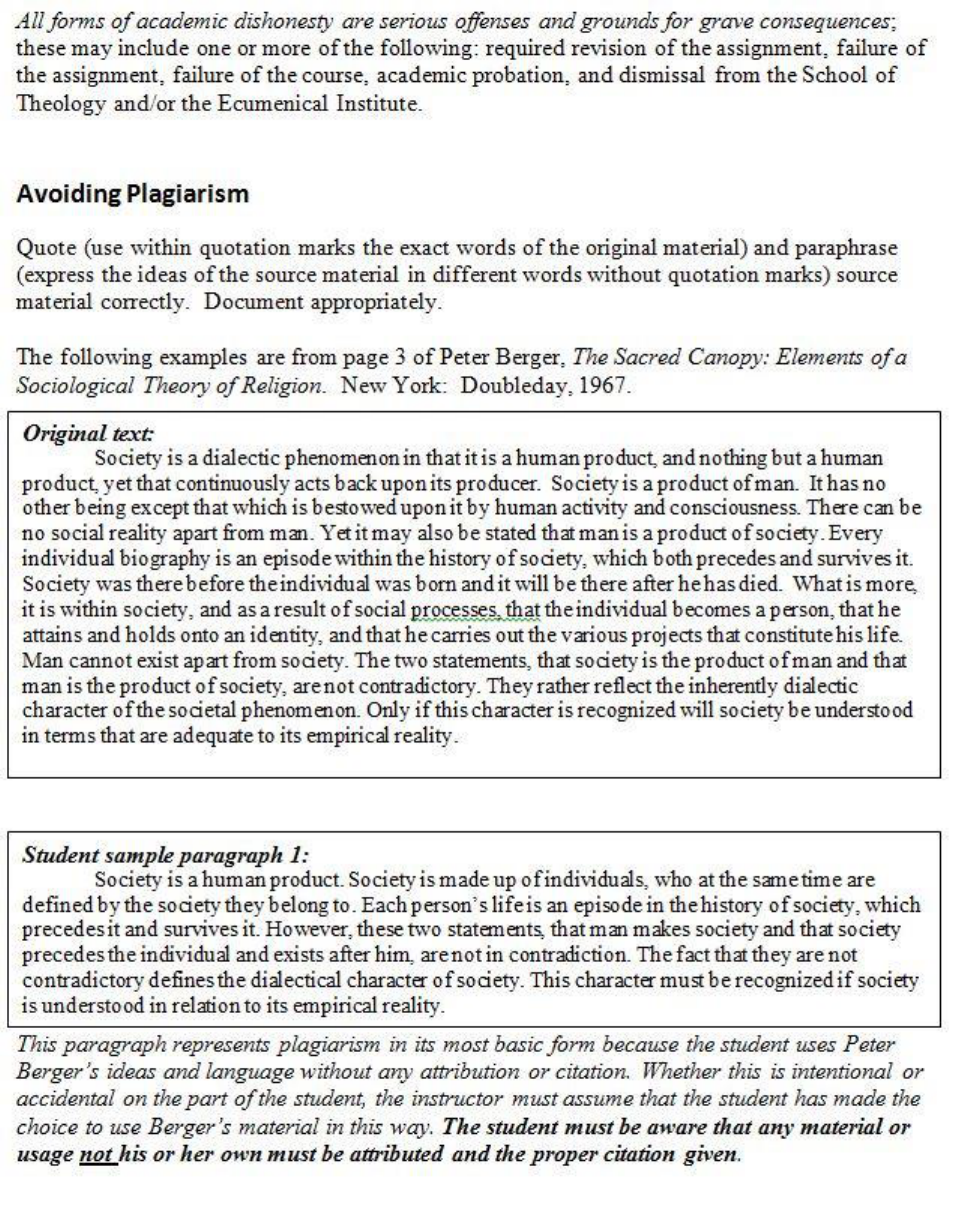

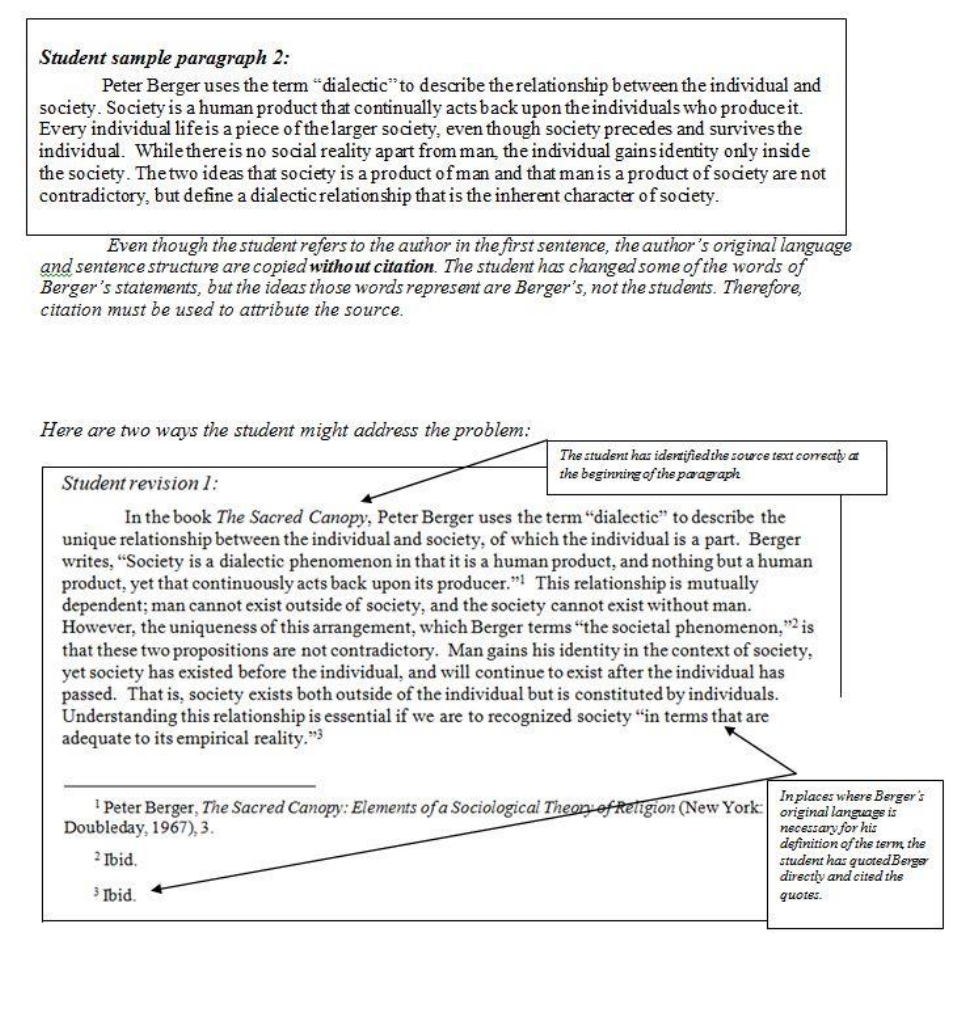

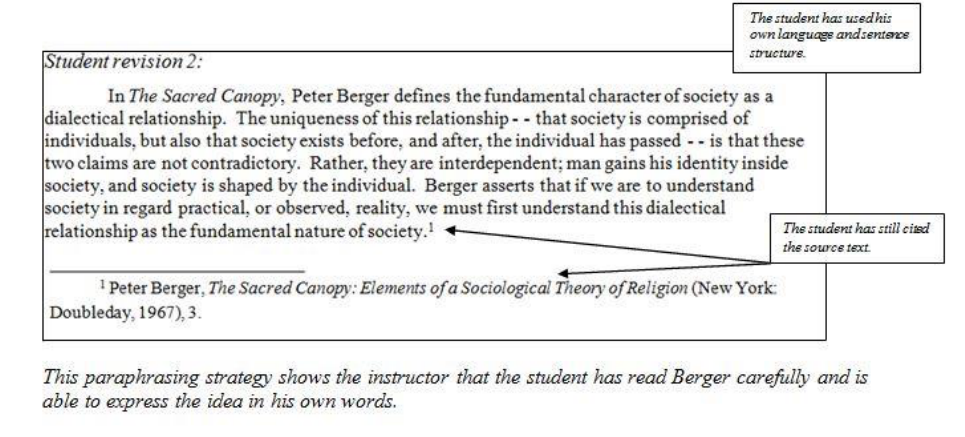

Avoiding Plagiarism ...................................................................................................................... 11

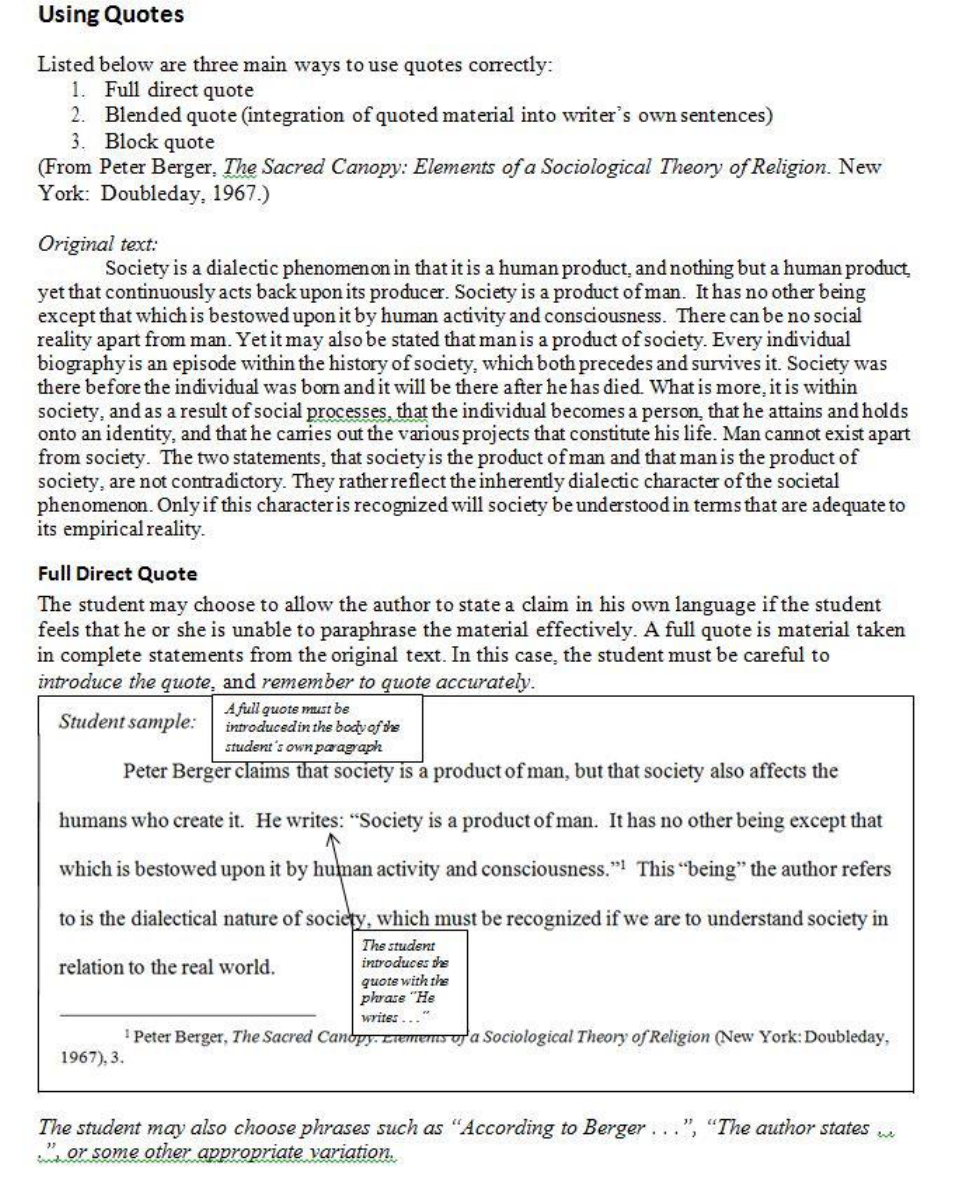

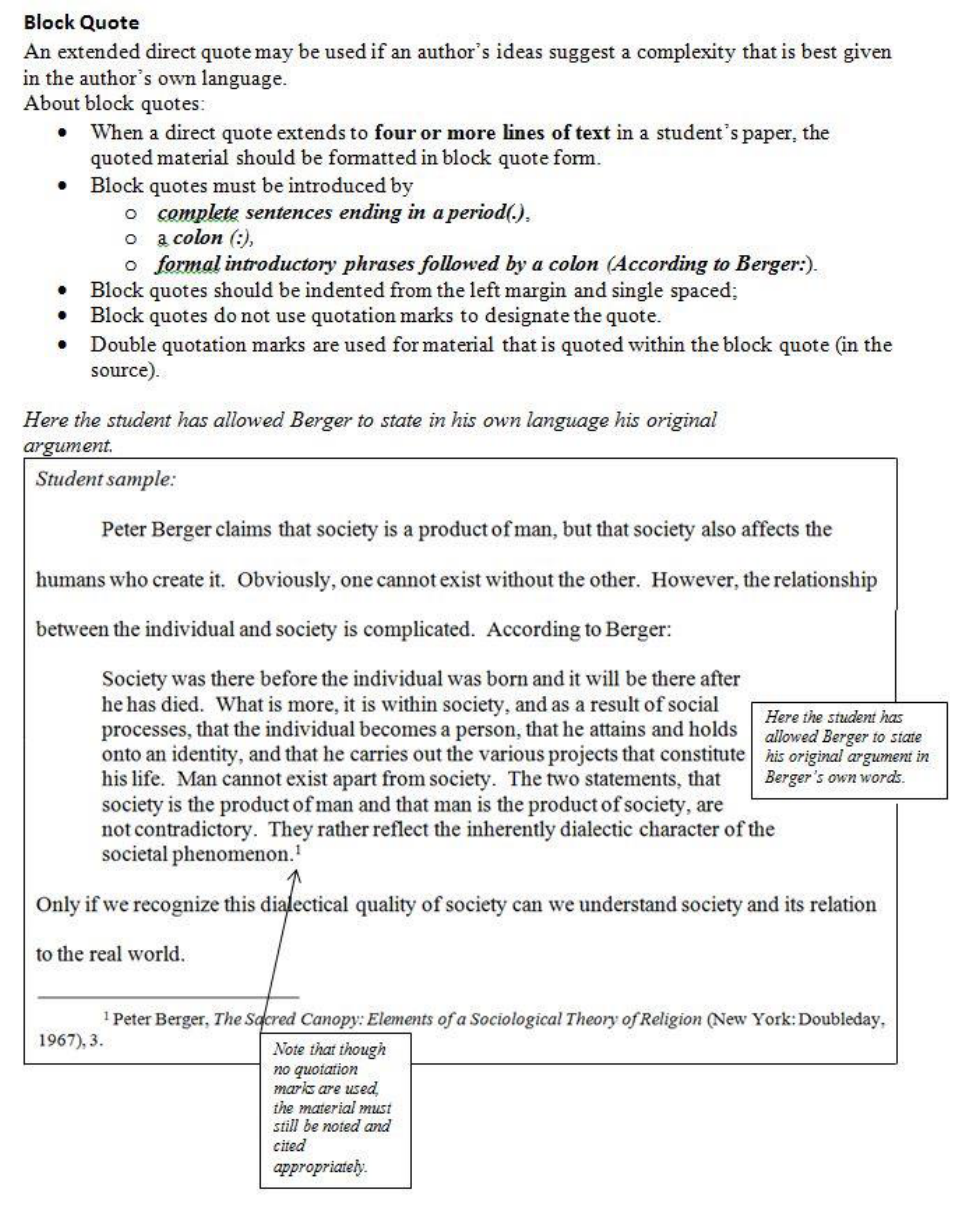

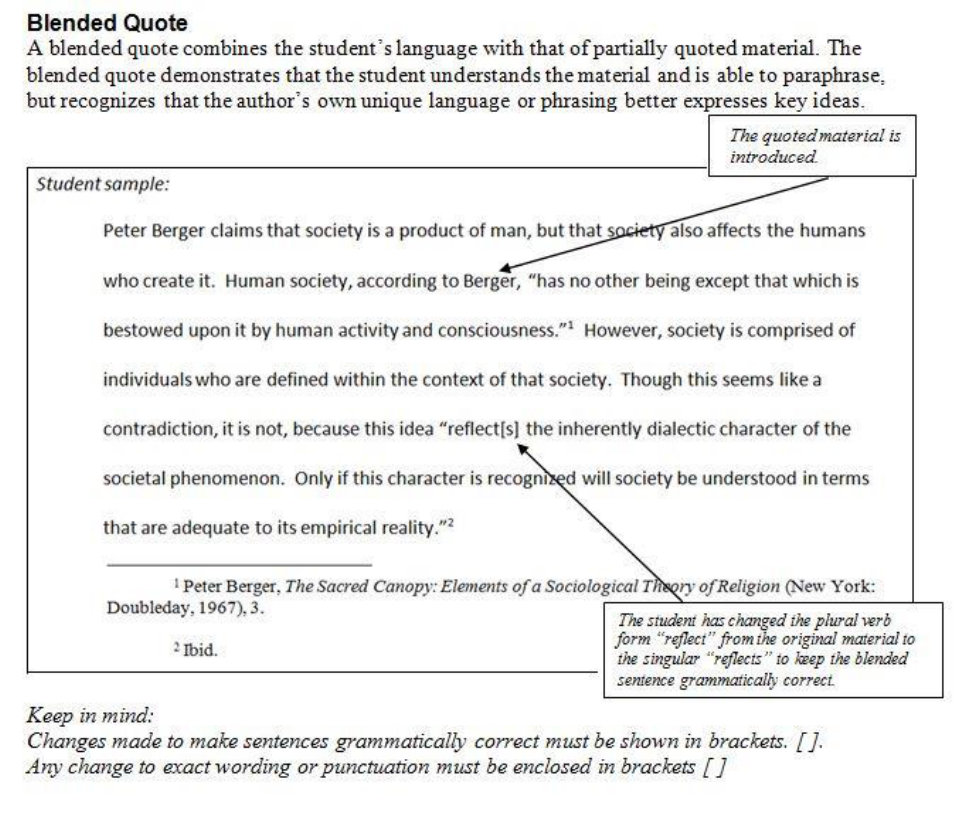

Using Quotes ................................................................................................................................. 14

Full Direct Quote .................................................................................................................................... 14

Block Quote ............................................................................................................................................ 15

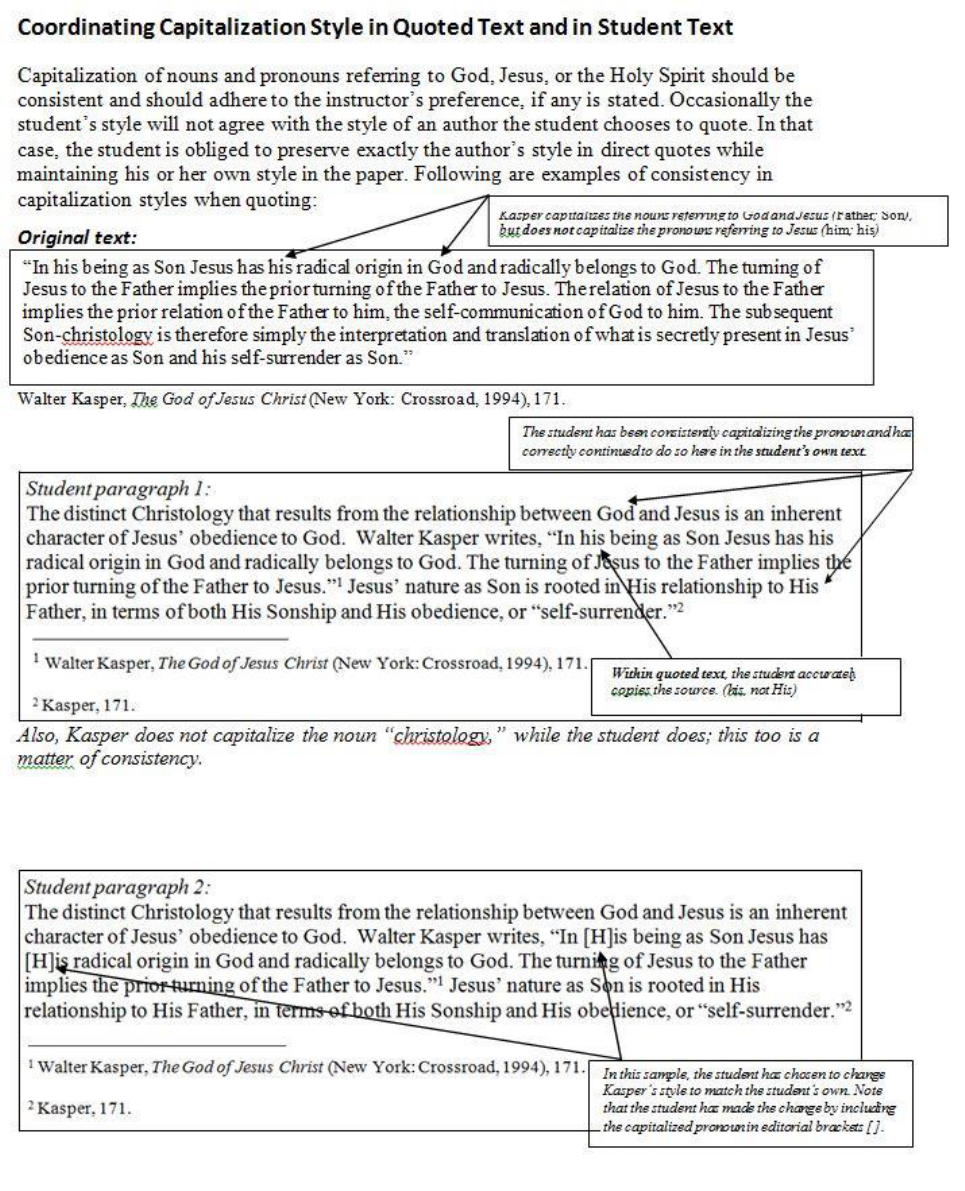

Coordinating Capitalization Style in Quoted Text and in Student Text ........................................ 17

Additional Note on Capitalization in General Text ....................................................................... 18

Turabian Formatting Checklist ...................................................................................................... 19

Chicago Manual Citation of Sources in Notes and Bibliographies ............................................... 20

Documentation of Sources ..................................................................................................................... 20

A Word About Turabian......................................................................................................................... 20

Organization of A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations by Turabian ........... 20

BOOKS: General Information................................................................................................................ 21

Examples of Turabian Citations: Books ................................................................................................. 22

ARTICLES: General Information .......................................................................................................... 23

Electronic, Unpublished, and Special Sources: General Information .................................................... 24

Citing Catholic Documents Using Turabian .......................................................................................... 26

Citing Dictionaries, Encyclopedias, Commentaries, Study Bibles, and the Catechism ......................... 28

Title Pages and Headings .............................................................................................................. 30

Appendix I: Student Writing Samples ........................................................................................... 31

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 1

Types of Academic Writing Used in Theological Study

Following are brief descriptions of typical assignments that theological students will complete.

The specific requirements of assignments will vary, depending on the class and the professor’s

preferences. Students are responsible for carefully following these requirements and asking for

clarification when necessary.

Case Study

Purpose: Write details of a specific incident or ruling and respond.

Requirements:

Evaluate key points of the case;

Analyze the significance of the resulting ruling or action;

Respond to instructor questions;

Write in the third person (he/she/it).

Organization:

Summarize the key points and the resulting ruling or action.

Evaluate the case by responding to instructor questions.

Critique (sometimes called Review or Critical Response)

Purpose: Summarize and evaluate another’s work, such as an article, book or film.

Requirements:

Extended summary (audience, purpose, thesis, development)

Evaluation of strengths, weakness, and effectiveness

Recommendations about the usefulness (?) of the work

Reflection on reviewer’s response

Citations informal. Page number in parenthesis after quotes and paraphrases.

Organization

Bibliographic Citation at the top of the page (unless indicated otherwise by professor)

Summary (minimum: one-third/ maximum: three-quarters of the critique)

Evaluation (minimum: one-quarter/ maximum: two-thirds of the critique)

Essay

Purpose: Extended academic paper which establishes a thesis, supports the thesis, and forms a

conclusion based on the support.

Requirements:

Introduction, thesis, support, conclusion;

Research and/or referring (?) to a specific text;

Third person (he/she/it)

Organization

Introduction with thesis

Supporting paragraphs

Conclusion

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 2

Exegesis Paper

Purpose: Explore the meaning of a passage from Scripture.

Requirements:

Explication: Through research and careful study, consider how the biblical text would

have been perceived by its original audience

Application: Consider what the pericope means to today’s reader

Developed thesis throughout the paper

Organized into the following sections:

Survey (Overview): introduces the passage and indication of the thesis that will be

developed

Contextual Analysis: describes the historical setting of the text and its literary contexts;

this is sometimes divided into separate historical and literary context sections

Formal Analysis:

1.

identifies the passage’s

literary form (e.g., lament, healing narrative, etc.)

characteristics of this genre as they influence meaning

2.

examines the structure and movement of the passage, including indications that

the passage can be considered to be a single sense-unit

Detailed Analysis: analyzes the text verse-by-verse or section-by-section, with special

attention to development of the paper’s thesis

Synthesis (Conclusion): brings together the various kinds of evidence collected to create a

conclusion that restates the thesis

Reflection: considers the implications of the text and/or the thesis of the paper for people

today

Homily / Sermon

Purpose: Explain the meaning of a biblical text and its application for the people of God today,

within the context of worship- necessary

Requirements:

Keep in mind that speaking forms are different than writing forms.

Keep sentence structure simple;

Make sure the relationship between the subject and object is clear;

Use language that the audience will understand;

Follow the instructions of the homiletics professor for the methods and assignment

guidelines.

Note: “homily” most often used by Catholics and “sermon”, message”, or “teaching” by

Protestants.

In-Class Exam

An in-class exam will ask the student to respond to a question, or series of questions, in a

specified time and specified length. In order to best meet the requirements of the in-class exam,

it is important to remember four points:

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 3

Understand what is being asked, and be sure to answer the question. A question might ask the

student to consider a number of options or to respond to several aspects of a topic. The question

might include language that qualifies the kind of response sought. The student should read the

question carefully and be sure to understand what is being asked. As simple as this may seem,

answering the question that is being asked—all parts of the question— is the student’s prime

responsibility.

Look for action verbs that direct the response. The question will include terms such as “analyze,”

“compare,” “reflect on,” etc., that tell the student how to approach the answer. These terms will

determine the specific methodology the student should employ when organizing the response.

Outline the answer before writing. Because of time limits, order the points of the answer

logically before writing. Outlining the answer serves two purposes: the outline serves as a guide

to ensure the answer is logically and effectively developed; and the outline provides for the

instructor an idea of the student’s intentions if the student does not have time to complete an

answer.

Allow time for outlining and proofreading. The student should allow five minutes of exam time

for each of these activities.

Journals

Purpose: Show the development of a student’s thinking as a result of readings, lectures,

experiences, etc.

Requirements:

As assigned by the professor. Be sure to note:

o Length

o Frequency

o Type of content

o Any other guidelines

Pastoral Narrative

Purpose: Describe your pastoral experience and its impact on you.

Requirements:

Describe :

o your response to the experience;

o the influence it has had on your ideas about self, God, and other life issues.

Evaluate your:

o interpersonal skills (relating with others);

o ability to take the initiative in meet the needs of others;

o ability to find creative solutions to problems.

Focus on who, what, when, how but NOT why.

o Do not assume the feelings or motivations of others unless they have been clearly

stated.

Reflect on your feelings about the experience.

Précis (See Summary)

Reflection / Reflection Paper

Purpose: Narrate, examine, and evaluate the writer’s personal observations and experiences of a

subject.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 4

Requirements:

Respond to readings, interviews, lectures, or experiences as assigned by the professor;

Respond to specific questions from the professor;

Organize, develop and support;

Use style and language appropriate to the assignment;

Paraphrase and summarize appropriately.

Organization:

Summarize or evaluate some part of the assigned material;

Relate this topic to the writer’s own experience or observation of life today.

Research Paper

Writers of research papers choose a topic, formulate a question to answer, collect information

from various sources, and present the answer to the question in written form. Best practices with

research papers include these:

The organization of the paper is clear to the reader. The paper contains an introduction, an

extended body, and a conclusion. For papers of more than a few pages, the use of subheadings

(section titles) throughout the paper can assist the writer to stay focused and the reader to follow

the paper’s structure.

The thesis is clearly stated;

The paper shows evidence of original thinking and analysis. Sources are used to support the

thinking that the writer has developed.

All information that is paraphrased or quoted is correctly identified. Quotes are accurate. Quoted

material is placed within quotation marks or block quoted form. Appropriate documentation

indicates the sources of information, interpretations, and quotations.

Documentation of sources follows Turabian’s Notes-Bibliography style, unless the teacher

specifies a different style. In addition to text references (footnotes, endnotes, or parenthetical

citations), all sources are identified in a list of sources, normally called the Bibliography or

Works Cited.

As in all academic writing, the paper uses standard American-English grammar, punctuation,

capitalization, and spelling; it evidences careful drafting, revision, editing, and proofreading.

The paper follows the length and format (title page, title, sections, etc.) requirements set out by

the professor.

Review (See Critique)

Sermon (See Homily / Sermon)

Summary (sometimes called Précis)

Purpose: Briefly describe another work, the work’s intended audience, purpose, thesis, and

development.

Organization:

Bibliographic citation placed at the top of the summary (unless the professor instructs

otherwise)

Citations are informal (page numbers are placed inside parentheses after quotes and

paraphrases.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 5

Verbatim

Purpose: Reproduce a conversation related to ministry and explore the content and meaning of

this conversation.

Requirements:

Dialogue;

Parenthetical description of physical gestures and other details;

Analysis of the conversation.

Effective Academic Writing

The following six characteristics of academic writing determine how well a writer’s ideas are

communicated to the reader. A writer who expresses his or her views clearly, concisely, and

precisely helps the reader understand the purpose and ideas of the paper or other assignment

without ambiguity or confusion.

Unity

Express the main idea for the writing assignment. There is usually a thesis statement for the

paper, a topic sentence (or clear topic) for each paragraph, and a conclusion that restates the

thesis. All ideas must be clearly related to the portion of the text. All parts must relate to the

thesis of the entire paper.

Support

Academic writing requires adequate and appropriate facts, examples, reasons, and arguments to

develop and support the main idea.

Coherence

Organize all the material in a logical order so that it is easy for the reader to follow. According to

the assignment, the ideas should be ordered logically. This could be by importance, time, space,

general to specific, specific to general, or by some other standard. Use transitional words and

phrases to show the reader the relationship of one idea to another.

Correctness

Proofread carefully to eliminate errors such as inaccurate or incomplete factual details, incorrect

or non-standard spelling, poor word choice, incorrect punctuation, capitalization errors, lack of

grammatical agreement, and incorrect or awkward sentence structure.

Documentation of sources is critical in academic writing, and it should be created according to

the required style, which at St. Mary’s is normally the Chicago Manual style as summarized in

Turabian. Quoted material should be copied exactly as it appears in the source; any changes that

are made must be indicated by editorial brackets: [ ].

Appropriate Style

Academic writing is usually moderately formal; whatever its level of formality, it benefits from

these qualities:

Focus: There is a clear central topic; everything in the paper contributes to developing

this topic or idea.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 6

Vitality: Use action verbs, direct phrasing, minimal passive voice (active: Paul broke the

window; passive: The window was broken), and other factors to create lively, energetic

prose. Avoid redundancy (unnecessary repeating of ideas).

Originality: The content may not be original, but the writer avoids clichés (“time will

tell”, “one step at a time”) and tired phrases and uses fresh images for clarity.

Smoothness: Wording and organization, especially transitions, are graceful and easy; they

avoid jolting the reader.

Parallelism: When words, phrases, or clauses are in pairs or series, they should be in

similar form. Here is an example of a non-parallel series:

Following Jesus’ crucifixion, the disciples were grief-stricken, confused, and they were afraid.

(adjective) (adjective) (subject + verb)

Correction:

Following Jesus’ crucifixion, the disciples were grief-stricken, confused, and afraid

(adjective) (adjective) (adjective)

Variety / Interest: The writer creates variety and interest by incorporating different

sentence patterns, metaphors, idioms, colorful words, appropriate repetition, and other

rhetorical devices. This should be done in moderation.

Precision: The writer uses appropriate factual material, accurately quoted or paraphrased,

to represent the ideas of others, as well as careful, precise wording to articulate his or her

own ideas. Precision is an especially important aspect of theological writing.

Scholarship

Present reasonable analyses, explanations, opinions, critiques of other, conclusions calmly,

not emotionally;

Use credible and respected sources;

Acknowledge different positions;

Support claims with evidence and careful argument;

Quote and paraphrase correctly in order to avoid plagiarism;

Construct citations and bibliographies correctly.

Inclusive Language

Writers should avoid language that makes assumptions about gender.

When those being described could be of either gender, consider these options:

Use gender-neutral terms

Use the plural form for nouns and pronouns

Include both male and female pronouns

Non-inclusive wording Gender-neutral alternatives

mankind, men (meaning males and females) humankind, people, humanity, human beings

policeman, policewoman police officer

mother, fathers parents, guardians, caregivers

girls, boys children, young people, teenagers

Each student planned his presentation. The students planned their presentations.

Each student planned his or her presentation.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 7

Examples:

Our congregation hopes to hire a parish nurse who has completed her training.

[Not all parish nurses are women.]

Possible solution: Our congregation hopes to hire a parish nurse who has completed training.

The wives of clergy will tour the city center during the conference.

[Not all clergy marry. Of those who do, not all are men; thus, the spouses may be male or female.

Further, it cannot be assumed that none of these people have a part in the conference, or that they

would all choose to take a tour.]

Possible solution: Spouses of clergy who wish to do so will tour the city center during the

conference.

Everyone must either write a thesis or take a comprehensive examination in order to receive his

master’s degree.

[Not all students are men. One solution, matching “everyone” with “their,” does not work

because “everyone” is considered a singular word and the pronoun “their” is plural; therefore,

these two words do not agree.]

Possible solutions:

All students must either write a thesis or take a comprehensive examination in order to receive

their master’s degrees.

All students must either write a thesis or take a comprehensive examination in order to graduate.

Members of the board will elect a chairman.

[Not all candidates for this position will be men.]

Possible solution: Members of the board will elect a chairperson.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 8

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 9

General Guidelines for Research Writing

Use correct form for citations and source lists; even periods, commas, and spaces matter.

Attention to these details is part of a scholarly habit of being careful, thorough, and precise.

Consult a variety of good scholarly sources—journals, books, and relevant websites, among

others—as appropriate for the nature of the assignment.

Unless directed otherwise by your professor, include only the works that are cited in the body of

the paper and/or notes in the bibliography.

Use enough sources to effectively support the paper’s overall thesis and its subordinate claims.

Be careful not to rely too much on quoted material. Strive for balance between your own

analyses and quoted or paraphrased material. Appropriate reference to source material will

generally result in approximately one to three footnotes per page of text.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 10

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 11

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 12

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 13

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 14

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 15

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 16

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 17

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 18

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 19

Turabian Formatting Checklist

General Format Requirements

Margins 8. x 11” paper; at least 1” on all four edges of the page

Typeface Times New Roman, Courier, or Helvetica font; 12 point font for the body of the

paper.

Spacing & Indentation

Double-space all text except block quotations.

No extra spaces between paragraphs

Indent at the beginning of each new paragraph.

Pagination Front Matter (usually just a title page): Centered, lower case Roman numerals in a footer.

Text: Numbered contiguously starting with page 1 in a header on the right.

Titles Bold, Centered

Title Page Title should be centered, double-spaced, ⅓ down the page, subtitle on separate

line.

Name, course code and course name, instructor name, and due date should be

centered, double-spaced, and ⅔ down the page

Footnotes (see “Chicago Manual Citation of Sources in Notes and Bibliographies,” pp 20-25)

Typeface 10 point font

Indentation indentation of the first line

Bibliography

Typeface 12 point font

Spacing Single-spaced within each entry, double-spaced between entries

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 20

Chicago Manual Citation of Sources in Notes and Bibliographies

(Many examples are from a guide compiled by Fr. Paul Zilonka & Dr. Michael Gorman or from Writing

Theology Well: A Rhetoric for Theological and Biblical Writers, 2006, by Lucretia B. Yaghjian.)

Documentation of Sources

In your research papers, it is important to provide accurate citation and complete bibliographical

documentation of your sources. Following are citation examples based on the guidelines found

in Kate L. Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, 8

th

ed.,

revised by Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, and University of

Chicago Press Editorial Staff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

A Word About Turabian

There is a book called The Chicago Manual; however, Kate L. Turabian, former dissertation

secretary of the University of Chicago, wrote a brief guide to The Chicago Manual’s methods of

documentation for academic writers. This became a book, A Manual for Writers of Term

Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. The current edition of this book is the standard reference

used at St. Mary’s Seminary & University, both in the School of Theology and the

Ecumenical Institute.

1

Within the Turabian reference, two variations of CM documentation are explained:

Notes-Bibliography Style

Parenthetical Citations-Reference List Style

At St. Mary’s, students use Notes-Bibliography Style. The sample notes* and bibliographic

entries here are based on Turabian’s 8

th

edition Notes-Bibliography Style.

*Terminology: “Note” stands for either footnotes or endnotes. The only difference between these two forms is that

footnotes appear at the bottom of the page where the cited material appears. Endnotes appear at the end of the text,

at the end of the document, chapter, or book, for example. Generally, footnotes are the preferred type of note at St.

Mary’s.

Organization of A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations by Turabian

Part 1: From Planning to Production

These chapters detail how to plan and conduct research and write a research paper. There is excellent

information here about forming a hypothesis, choosing and learning from sources, drafting, and revising.

Part 2: Source Citation

Chapter 15 is a general introduction to citing sources. Chapters 16 and 17 show how to document sources

in the Notes-Bibliography Style. These are the chapters St. Mary’s students should consult.

Chapters 18 and 19 explain the Parenthetical Citations-Reference List Style of documentation. This is

NOT the standard style used at St. Mary’s. St. Mary’s students do NOT need to consult these chapters

unless professors request use of Chicago Manual parenthetical citations.

1

Some disciplines require other documentation systems such as MLA (Modern Languages Association) or

APA (American Psychological Association). When that is the case, please consult the appropriate references.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 21

Part 3: Style

In these chapters, students will find advice on various stylistic topics ranging from spelling to

incorporating tables and figures into the document. St. Mary’s students should carefully review Chapter

25 on correct ways to quote sources and avoid plagiarism.

Below are a few typical types of entries in their Note and Bibliographic formats. Consult chapters 16 and

17 of Turabian for more detail, especially for types of entries not covered here.

BOOKS: General Information

Footnotes or Endnotes for Citations from and References to Books

The first line only is indented. Generally, a comma separates items from each other. Each note

ends with a period.

Author’s first name + last name, Book title [italicized

2

]: subtitle [if any, also italicized and preceded by a

colon], Name of editor or compiler or translator [if any], Number or name of edition [if other than the first], Name

of series [if any; not italicized, with headline capitalization], volume or number in the series (Publishing information

within parentheses — Place of publication [omit state or country for major cities] + colon: Publisher [may omit

“Press” if not a University Press; also omit “The” when it is the first word and words or abbreviations such as

“Co.”], Date), Page number(s) of specific citation [Do not use “page” or abbreviations such as p. or pp.].

2

Jon D. Levenson, The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son (New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press, 1993), 129.

Shortened Form for Subsequent Footnotes

For notes that follow immediately after a note for the same source, the abbreviation Ibid. may be

used, unless the professor instructs otherwise. If all the information except the page number is

the same, use Ibid., page number.

3

Ibid., 134.

For subsequent notes that do not follow immediately after notes for the same source, use a

shortened form that includes the author’s last name, a shortened form of the title, and the page

reference.

11

Levenson, Death and Resurrection, 128.

Bibliography Format for Books

The first line begins at the left margin; subsequent lines are indented. Generally, a period

separates items. Each entry ends with a period.

Author’s last name, first name. Book title [italicized]: subtitle [if any; also italicized and preceded by a colon]. Name

of editor or compiler or translator [if any]. Number or name of edition [if other than the first]. Name of

series [if any; not italicized]. Volume or number in the series. Publishing information with no parentheses

— Place of publication [omit state or country for major cities]+ colon: Publisher [may omit ‘Press’ if not a

University Press], Date [most recent year if there are multiple years given].

Levenson, Jon D. The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,

1993.

2

When information is being written by hand or italicization is not available, the alternate method of

identifying book and periodical titles is to underline. DO NOT underline when italics are available.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 22

Examples of Turabian Citations: Books

Simple book

Note

2

Craig R. Koester, Symbolism in the Fourth Gospel (Minneapolis:

Fortress, 1995), 21.

Bibliographic Entry

Koester, Craig R. Symbolism in the Fourth Gospel. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995.

Book in a numbered series with editor other than the author

Note

2

Francis J. Moloney, The Gospel of John, Sacra Pagina 4, edited by

Daniel J. Harrington (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1998), 129.

Bibliographic Entry

Moloney, Francis J. The Gospel of John. Sacra Pagina 4, edited by Daniel J.

Harrington. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1998.

Book in a numbered series when author is also editor

Note

3

Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew, Sacra Pagina 1

(Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1991), 164.

Bibliographic Entry

Harrington, Daniel J. The Gospel of Matthew. Sacra Pagina 1. Collegeville, MN:

Liturgical, 1991.

Book in which author’s work is translated or edited by another

Note

2

Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the Gospel of John, ed. Francis

J. Moloney (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 125.

Bibliographic Entry

Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the Gospel of John. Edited by Francis J.

Moloney. New York: Doubleday, 2003.

Two authors [here also in a series with an editor]

Note

2

Philip J. King and Lawrence E. Stager, Life In Biblical Israel, Library of

Ancient Israel, ed. Douglas A. Knight (Louisville: Westminster John Knox,

2001), 135.

Bibliographic Entry

King, Philip J. and Lawrence E. Stager. Life In Biblical Israel. Library of Ancient

Israel, edited by Douglas A. Knight. Louisville: Westminster John Knox,

2001.

More than three authors

Note

2

Bruce C. Birch et al., A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament

(Nashville: Abingdon, 1999), 136.

Bibliographic Entry

Birch, Bruce C., Walter Brueggemann, Terence E. Fretheim and David L.

Petersen. A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament. Nashville:

Abingdon, 1999.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 23

ARTICLES: General Information

Footnotes or Endnotes for Citations from and References to Articles

The first line only is indented. Generally, a comma separates items from each other. Each note

ends with a period.

Author’s first name + last name, “Article Title: subtitle [if any, also placed within quotation marks and

preceded by a colon],” Title of Journal [italicized] Volume, no. Number [if either or both], (Date of Publication):

Page number of specific citation [do not use the word “page” or abbreviations such as p. or pp.].

2

Michael W. Harris, “African American Religious History in the 1980s: A Critical Review,”

Religious Studies Review 20, no. 4 (1994): 265.

Shortened Form for Subsequent Footnotes

[Note: Some faculty members do not allow Ibid. or restrict the use of Ibid. to same page footnotes

only. Please check with your professor.]

Use Ibid. for notes that follow immediately after notes for the same source. For other

subsequent notes, use a shortened form that includes the author’s last name, a shortened form

of the title, and the page reference. [Note placement of comma inside end quotation mark

after the article title.]

2

Harris, “African American Religious History,” 275.

Bibliography Format for Articles

The first line begins at the left margin; subsequent lines are indented. Generally, a period

separates items. Each entry ends with a period.

Author’s last name, first name. “Article Title [including colon and subtitle if any].” Title of Journal Volume, no.

Number [if either or both] (Date of Publication): xx-yy (Range of pages for entire article).

Harris, Michael W. “African American Religious History in the 1980s: A Critical Review.” Religious

Studies Review 20, no. 4 (1994): 263-75.

Examples of Turabian Citations: Articles

Article in a journal

Note

2

Xavier Léon-Dufour, “Reading the Fourth Gospel Symbolically,” New

Testament Studies 27 (1980-81): 442.

Bibliographic Entry

Léon-Dufour, Xavier. “Reading the Fourth Gospel Symbolically.” New

Testament Studies 27 (1980-81): 439-56.*

*Note: The colon shown here is used before page numbers only for journal

articles; for books, chapters in books, etc., a comma is used.

Signed Article in Edited Book/Encyclopedia/Dictionary

Note

2

Richard J. Dillon, “Acts of the Apostles,” in The New Jerome Biblical

Commentary, ed. Raymond E. Brown et al. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall,

1990), 745.

Bibliographic Entry

Dillon, Richard J. “Acts of the Apostles.” In The New Jerome Biblical

Commentary, ed. Raymond E. Brown, Joseph A. Fitzmyer, and Roland E.

Murphy. 722-767. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 24

Electronic, Unpublished, and Special Sources: General Information

Footnotes or Endnotes for Citations from and References to Articles in Online Journals The

first line only is indented. Generally, a comma separates items from each other. Each note includes

the URL and Date of Access and ends with a period. For articles that have a DOI, eg

10.1086/660696, add “http://dx.doi.org/” before the DOI and use it in the place of a URL. For

example: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/660696. Database names may be used instead of a URL.

Author’s first name + last name, “Article Title: subtitle [if any, also placed within quotation

marks and preceded by a colon],” Title of Journal [italicized] Volume, no. Number [if either or

both], (Date of Publication), Page Number [if available] OR under “Descriptive

Locator, [if necessary to give reader location; an example would be a heading that appears above

the text],” accessed Month dd, yyyy [date on which you read the electronic source], URL.

2

Hanna Stettler, “Sanctification in the Jesus Tradition,” Biblica 85 (2004): 265, accessed

April 3, 2005, http://www.bsw.org/project/biblica/bibli85.html.

Shortened Form for Subsequent Footnotes

Use Ibid. for notes that follow immediately after notes for the same source. For other subsequent

notes, use a shortened form that includes the author’s last name, a shortened form of the title, and

the page reference. [Note placement of comma inside end quotation mark after the article title.]

2

Stettler, “Sanctification,” 265.

Bibliography Format for Articles in Online Journals

The first line begins at the left margin; subsequent lines are indented. Generally, a period separates

items. Each entry contains the URL and access date and ends with a period. For articles that have

a DOI, eg 10.1086/660696, add “http://dx.doi.org/” before the DOI and use it in the place of a

URL. For example: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/660696. Database names may be used instead of a

URL.

Author’s last name, first name. “Article Title [including colon and subtitle if any].” Title of

Journal Volume, no. Number [if either or both] (Date of Publication): xx-yy (Range of

pages for entire article, if available). Accessed [month dd, year]. URL/database.

Stettler, Hanna. “Sanctification in the Jesus Tradition.” Biblica 85 (2004): 153-78. Accessed

April 3, 2005. http://www.bsw.org/project/biblica/bibli85.html.

Note: URLs are lengthy; sometimes it is necessary to insert a space into the URL so that the lines

in the citation can break normally. Insert the space between parts of the URL, never in the middle

of a “word.”

Other Electronic Sources

For information on documenting other electronic sources such as electronic books, websites, and

online reference works, please consult Turabian, primarily chapters 16 and 17, with special

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 25

attention to 15.4, 16.1.7, 17.1.7, 17.1.8, 17.1.10, 17.2.7, 17.5.9, 17.7, 17.8.6, and 17.9.13.

Unpublished Sources

Generally, instructors do not require course lectures or class discussions to be cited as source

material. However, lectures outside of class, as well as personal interviews, may be used a source

material and must be cited. Unpublished sources may be used so long as they are cited. A typical

citation will need the author’s name, the title of the work (if there is one), what it is (eg.

manuscript, journal, photograph, letter, etc.), date, and where it can be found.

Author’s last name, first name. “Title [including colon and subtitle if any].” Document type,

where found/given, date.

Smith, Jane J. “St. Mary’s: An Historical Analysis.” PhD diss, St. Mary’s Seminary &

University, 2016.

For Footnotes:

Auther’s first name last name, “Title [including colon and subtitle if any],” document type,

where found/given, date.

2

Jane J. Smith, “St. Mary’s: An Historical Analysis,” PhD diss, St. Mary’s Seminary &

University, 2016.

Personal Interview

In citations for interviews and personal communications, the name of the person interviewed or

the person from whom the communication is received should be listed first. This is followed by

the name of the interviewer or recipient, if given, and supplemented by details regarding the

place and date of the interview/communication. Unpublished interviews and personal

communications (such as face-to-face or telephone conversations, letters, e-mails, or text

messages) are best cited in text or in notes rather than in the bibliography:

2

Fr Thomas Burke in discussion with the author, September 2013.

3

Fr Edward Griswold, e-mail message to the author, September 2013.

Special Types of Sources

For use of the Bible and other sacred texts, see Turabian 17.5.2 and 24.6. Cite biblical sources

parenthetically or in notes, using traditional or shortened abbreviations for the names of books and

Arabic numerals for chapters and verses and the version on the first reference: 1 Cor. 6:1-10

(NAB). For use of encyclopedias and dictionaries, see Turabian 17.5.3. Usually, these sources will

be cited in notes, but not in bibliographies. For sources and information not covered in Turabian,

see the SBL Handbook of Style (Hendrickson, 1999), which is available in the library.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 26

Citations of Catholic Sources Using Turabian

Papal Documents

Note:

10

Pope Benedict XVI, Encyclical Letter. Caritas in Veritate [Charity in Truth] (Vatican /

Washington, DC: USCCB, 2009), 3.

Bib: Benedict XVI, Pope. Encyclical Letter. Caritas in Veritate [Charity in Truth]. Vatican /

Washington, DC: USCCB. 2009.

Note:

11

Pope John Paul II, Apostolic Exhortation, Catechesi Tradendae [Catechesis in Our Time]

(Vatican / Washington DC: USCCB, 1979), 18.

Bib: John Paul II, Pope. Apostolic Exhortation, Catechesi Tradendae [Catechesis in Our

Time].Vatican / Washington, DC: USCCB. 1979.

Note:

12

Pope John Paul II, Apostolic Letter, Rosarium Virginis Mariae [On the Most Holy Rosary]

(Vatican / Washington, DC: USCCB, 2002), 25.

Bib: John Paul II, Pope. Apostolic Letter, Rosarium Virginis Mariae [On the Most Holy

Rosary].Vatican / Washington: USCCB. 2002.

Note:

13

Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Letter. Humani Generis [Concerning Some False Opinions

Threatening to Undermine the Foundations of Catholic Doctrine] (Vatican, 1950), 12.

Bib: Pius XII, Pope. Encyclical Letter. Humani Generis [Concerning Some False Opinions

Threatening to Undermine the Foundations of Catholic Doctrine]. Vatican. 1950.

Roman Curia

Note:

14

Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, Instruction,

Redemptionis Sacramentum [Instrucion on certain matters to be observed or to be avoided

regarding the Most Holy Eucharist] (Vatican, 2004), 87.

Bib: Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Instruction,

Redemptionis Sacramentum [Instrucion on certain matters to be observed or to be avoided

regarding the Most Holy Eucharist]. Vatican. 2004.

Note:

15

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), Doctrinal Document, Dignitas Personae

[Instruction on Certain Bioethical Questions] (Vatican, 2008), 12.

Bib: Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). Doctrinal Document, Dignitas Personae

[Instruction on Certain Bioethical Questions]. Vatican. 2008.

Note:

16

Congregation for Catholic Education. “Guidelines for the Use of Psychology in the

Admission and Formation of Candidates for the Priesthood” (Vatican, 2008), 2.

Bib: Congregation for Catholic Education. “Guidelines for the Use of Psychology in the Admission

and Formation of Candidates for the Priesthood”. Vatican. 2008

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 27

Note:

17

Synod of Bishops. XII Ordinary General Assembly: The Word of God in the Life and

Mission of the Church, “Message to the People of God at the Conclusion of the XII Ordinary

Assembly (Vatican, 2008), 8.

Bib: Synod of Bishops. XII Ordinary General Assembly: The Word of God in the Life and Mission

of the Church, “Message to the People of God at the Conclusion of the XII Ordinary

Assembly. Vatican. 2008.

Vatican Documents

Note:

18

Vatican Council II, Gaudim et Spes [Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern

World]. In Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents, vol. 1, ed.

Austin Flannery, O.P., 5th ed., rev. ed. (Northport, NY: Costello Publishing Company, 2004), 10.

Bib: Vatican Council II. Gaudim et Spes [Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern

World]. In Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents. Vol. 1. Edited

by Austin Flannery, O.P., 910-911. 5th ed. Rev. ed. Northport, NY: Costello Publishing

Company, 2004.

USCCB Documents

Note:

19

USCCB. Go and Make Disciples, A National Plan and Strategy for Catholic Evangelization

in the United States (1993; repr., Washington, DC: USCCB, 2002), 45.

Bib: USCCB. Go and Make Disciples, A National Plan and Strategy for Catholic Evangelization in

the United States. 1993. Reprint, Washington, DC: USCCB, 2002.

Classical Theological Works

Note:

20

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae (henceforth cited as ST) I, 103.4, trans. the Fathers of

the English Dominican Province, (New York: NY, Benziger Brothers, 1948).

Abbreviated Note:

21

ST I-II, 90.1

Bib: Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologiae. Translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican

Province. New York: NY, Benziger Brothers, 1948.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 28

Citation of Theological Dictionaries, Commentaries, Study Bibles, and Catechism

Theological Dictionary / Encyclopedia:

Note: Rosemary Radford Ruether, “Feminist Theology,” in The New Dictionary of Theology, ed.

Joseph A. Komonchak, Mary Collins, and Dermot A. Lane (Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, 1988),

391-96.

Bib: Ruether, Rosemary Radford. “Feminist Theology.” In The New Dictionary of Theology. Edited

Komonchak, Joseph A., Mary Collins, and Dermot A. Lane. Wilmington, DE: Michael

Glazier, 1988. 391-96.

Note: John Drury, “Luke,” in The Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. Robert Alter and Frank Kermode

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1987), 418-39.

Bib: Drury, John. “Luke.” In The Literary Guide to the Bible. Edited Alter, Robert and Frank

Kermode. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1987. 418-39.

Biblical Commentary

multivolume work

Note: Richard N. Longenecker, “Acts,” in John and Acts, vol. 9, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary:

With the New International Version, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1981), 205.

Bib: Longenecker, Richard N. “Acts.” In John and Acts. Volume 9, The Expositor’s Bible

Commentary: With the New International Version. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1981.

Note: Joseph A. Fitzmeyer, The Gospel According to Luke, vol. 28, The Anchor Bible (Garden City,

NY: Doubleday, 1983), 75.

Bib: Fitzmeyer, Joseph A. The Gospel According to Luke. Volume 28 of The Anchor Bible. Garden

City, NY: Doubleday, 1983.

single volume

Note: Jane Schaberg, “Luke,” in The Woman’s Bible Commentary, ed. Carol A. Newsom and Sharon

H. Ringe (Louisville: Westminster / John Know, 1992), 275.

Bib: Schaberg, Jane. “Luke.” In The Woman’s Bible Commentary. Edited Newsom, Carol A. and

Sharon H. Ringe. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1992. 275-92.

Study Bibles (Bible passages should be cited by chapter and verse, not by page number)

Note: J.D. Douglas, ed, The New Greek-English Interlinear New Testament (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale,

1990).

Bib: Douglas, J.D., Editor. The New Greek-English Interlinear New Testament. Wheaton, IL:

Tyndale, 1990.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 29

Note: Wayne A. Meeks, ed, The Harper Collins Study Bible, New Revised Standard Version (New

York: Harper Collins, 1989).

Bib: Meeks, Wayne A., General Editor. The Harper Collins Study Bible, New Revised Standard

Version. New York: Harper Collins, 1989.

Catechism of the Catholic Church

Note: Catholic Church, “The Effects of Confirmation,” in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2

nd

ed. (Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012), no. 1303.

Bib: Catholic Church. “The Effects of Confirmation.” Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2

nd

edition.

Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012.

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 30

Title Pages and Headings

Following are title pages and headings that can serve as models. These are not standard required

forms; individual professors may have specific requirements for when to use title pages, when to

use headings on the first page of the paper, and what form these should take.

Title Page (based on Turabian guidelines)

Center the title about one third of the

way down the page.

If there is a subtitle, place a colon after

the main title and type the subtitle on

the next line.

About a third of the way from the bottom

of the page, type your name and other

information requested by the instructor

such as the course number and date.

Do not insert page numbers on the title page.

Headings on First Page of Paper

Turabian notes that titles may be on

the first page of a paper, but the book

does not provide a model.

The example illustrated to the right

includes the student’s name, the class

identification, and the date in a heading.

The title of the paper is centered below

the heading. Note the colon between the

title and subtitle.

For some assignments, a citation will be

placed where the title is on this sample.

In this case, the title of the assignment

(i.e., Summary) may appear in the heading.

Major Forms of Christian Art:

From Mosaics to Stained Glass

Lee Witherall

SP702.1

May 5, 2010

Lee Witherall

SP702.1

May 5, 2010

Major Forms of Christian Art:

From Mosaics to Stained Glass

St Mary's Seminary & University Student Writing Guide 31

Appendix I: Sample Papers

Book Review

Comparison

Critique

Pastoral Narrative

Research Paper

Exegesis

1

Book Review

Burtchaell, James Turnstead. For Better or Worse: Sober Thoughts on Passionate Promises.

Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1985

In his book For Better, For Worse, James Tunstead Burtchaell offers a realistic look of

what it takes to sustain a fruitful marriage and family. In his no holds barred account of marriage

and family life, he does not mince words as he describes that to be successful in marriage, one

must be self-sacrificing and willing to give his or herself totally to the relationship. He makes it

clear that there are no guarantees in marriage and that the commitment promised at the beginning

of the marriage is a commitment of life and death. The words “’til death do us part” represent a

sobering reality that all couples must face when entering marriage. There is no way to see the road

ahead, and this means accepting your partner in all that he or she is, and will be. The only way to

do this is to lay one’s life on the line and say, “I give you and our children my whole self and I

hold nothing back.”

Burtchaell begins with a treatment of marriage that is not for the faint of heart. As a matter

of fact, he even makes the argument that what Catholics have in mind when they talk of Christian

marriage is actually nothing short of crazy. He also mentions that Catholics do not govern

marriage, or even claim an exclusive enterprise on marriage, what we do is preach marriage. We

preach a marriage that can only be understood in light of our faith. Burtchaell makes the point that

“it would be senseless for Catholics to urge on others our vision of marriage if they do not share

our vision of Jesus and faith” (Burtchaell, 20).

Having established that our understanding of marriage must be seen in light of our faith in

Jesus Christ, he goes onto explain how extreme this faith really is. In the 19

th

chapter of

Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus expresses how extreme his ministry is in two consecutive narratives. The

first is Jesus’ denial of divorce which had previously been allowed by the Mosaic Law. In Mt.

2

19:6 Jesus says, “What God has united man must not divide,” and follows it up with “The man

who divorces his wife and marries another is guilty of adultery against her” (Mt. 19:9). Following

this Jesus relates the story of the young man who asks what it takes to be a disciple. While the

young man fulfills the commandments, he nonetheless falls short, as he is not able to give up

everything and follow Jesus.

According to Burtchaell the teaching on divorce and the story of the young man both

represent the radical commitment of Christian marriage. In these two stories, Jesus is breaking

with tradition. Tradition held that “When a young man became an adult he accepted his divinely

specified obligations. He entered life with open eyes; he knew what he was undertaking”

(Burtchaell, 22). In this way it seems that the law actually provided a level of security and eased

commitment, as one knew what to expect. However, Jesus’s teaching was much more radical, he

was calling people to move away from a life governed by the law to a life of dedication to other

people. While this new teaching had fulfilled the law, it was actually more demanding than the

law itself.

People were now being called to a life that was not planned out, and to which they could

never know what was demanded of them. It was a radical commitment because it was saying, “I

follow you regardless of what lies ahead and with the understanding that what lies ahead is not

likely what I expect.” Burtchaell relates this to marriage. He explains that when a Jew married in

Jesus’ time, he knew what was ahead of him. His future was essentially prescribed and he was

able to accept this commitment, because he entered with eyes wide open. What Jesus did in

renouncing divorce was to eliminate a marriage of caution and require a person to bind themselves

to another person, rather than to a set of conditions. This was a radical move as it was inherently a

risk. One cannot calculate the future, and therefore, has to enter a marriage where each one’s

claim on the generosity of the other was “open-ended” (Burtchaell, 24).

3

This “open-ended” commitment to marriage will be the underlying theme in marital and

family commitment throughout the book. It is the radical commitment of Jesus Christ to the

Father, and the radical commitment of the disciples to Jesus. It calls for a completely open pledge

of husband to wife, wife to husband, and parents to children. It is a total self-surrender to those

who one commits to, and it is a pledge made without any future guarantees. The nature of the

pledge is very difficult as it is made with unspecified terms of service. This is significant to

Burtchaell as he argues that it is through pledging that humans reach full maturity.

Having established the importance of the pledge, Burtchaell continues his treatment of

Christian marriage with the understanding that if one is going to make the radical pledge that is

necessary for a fruitful marriage, then the courtship is crucial to the marriage. The courtship

according to Burtchaell is less about who the person marries, than how they marry. Courtship is

not only about coming to believe someone is right for you, rather, it is about what makes you right

for each other. Each person needs to honestly be asking themselves, what draws me to him or her,

while being open to all answers, good and bad. It is in this stage when it is wise to meet family

members and friends that offer honest information about one’s potential spouse, and to get their

take on the relationship. A courtship experienced only between two partners is one that is more

likely to fail in marriage.

It is also in the context of courtship, especially in modern times, that sex is introduced into

the relationship. Here, Burtchaell argues that the Catholic tradition is often misunderstood in its

views of sex. The Church is often seen as very negative in the area of sex, while Burtchaell argues

that it is actually the opposite. He offers a brief but poignant summary of the churches teaching on

sex.

The Church has two fairly simple teachings about sex. The first is that sex is supposed to

mean what marriage is supposed to mean. The second is that sex reveals meaning

(Burtchaell, 33).

4

The idea that sex is an expression of love seems to be the overarching understanding of sex in

modern times. The Church not only disagrees with this premise, she offers an expanded view of

the meaning of sex.

There are many other expressions of love besides sex, and sex is not necessary for love.

Rather in the marital life, sex is a celebration of this love. It is fruitful only in the context of the

pledge to one another. Sex is one physically intimate way of saying I give myself entirely to you,

and you give yourself entirely to me. Sex in the context of the pledge that is marriage has no

inhibitions and is open to all possibilities. It is an unyielding sharing of one’s privacy with each

other, while being completely open to childbearing. This is why sex should come with marriage,

not before it. It is only after the man and woman have pledged their entire lives to each other that

they can be open to pledging their entire lives to children.

The total self-giving of marriage which is demonstrated in sex allows the couple to be open

to total a total self-giving to their children. Therefore, sex in marriage has to be open to

childbearing, or the self-giving is never complete. The uninhibited possibility of childbearing is

another way that the couple is totally self-available to one another. Burtchaell discusses Pope Paul

VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae in his discussion of childbearing, and actually argues that while the

Pope’s motives were good, he misses the mark. The Pope renounces artificial birth control, but

allows for the natural or rhythm method of birth control.

Burtchaell’s issue with this treatment of contraception is that it is not about whether a

singular act of sex is open to conception, but whether the entire life time of sex between a couple is

open to family. Children have a claim on a person’s life just as a husband and wife have a claim

on each other’s life. And for a couple to be open to children, they have to be able to make a pledge

to the child as well. This pledge, like the pledge that they have made to each other, is also

5

unconditional. “Let a couple determine how they will welcome children, provided they have a

welcome for children” (Burtchaell, 39).

After describing the “crazy” commitment that marriage really takes and the sacrifice of self

that is necessary to have a family, Burtchaell discusses the decision to get married in more detail.

For Burtchaell the decision to marry is based on time, and getting to know one another. However,

he argues that this “time,” which takes place during the courtship, is not just time spent with the

person you are courting in one-on-one romantic situations, but rather experiencing the person in

the midst of real life. A romantic dinner date between two people reveals completely different

things than painting a porch together, or hosting a dinner together. These are atmospheres where

true personalities come out, allowing the partners to experience previously undisclosed realities

about each other.

He also encourages couples to see how the other person is at home. The environment in

which they met can present them completely different from the environment where they grew up.

And, often the roots of their upbringing are still firmly attached. He suggests meeting the family

of one’s partner and talking to members of the family who are willing to be candid about the

partner. This takes courage, but Burtchaell believes that this will pay off in the long run. So often

it seems that the family new all along that a marriage would not work out, but because the future

spouse never got to know them, or because they kept silent, a disaster ensued that could have been

averted.

It is not enough, however, just to experience your partner in different social settings and to

meet their family. It is also important that you get to know what your partner is thinking. A

couple who plans to get married should ask each other questions about politics, world issues, and

core beliefs. Burtchaell argues that these are the things that often come out after the marriage and

cause serious problems down the road. He also argues that differences in opinion on major issues,

6

politics, and beliefs are not deal breakers, but they are things that need to be addressed prior to the

marriage. He says that quite often, with work ,these issues can be reconciled, but for this to be

done in a healthy manner, it is better if they are brought to light before the marriage.

After considering what it takes for a proper courtship, Burtchaell argues that it is often the

case in marriage that a person gets what they deserve. Marriages are often made up of one giver

and one taker. This forms a codependent relationship where the giver typically gives into the

whims of the taker, and then becomes the martyr in closed conversations with close friends. It

seems in society that the giver is the victim, while Burchaell argues that they are actually both

victims, and often the taker turns out to be the victim. He says that givers enter into relationships

with people who are takers, because it satisfies an unhealthy need in the giver. Many of these

people are not ready for marriage and have a lot of maturing to do before they are ready. He

argues that true self-possession is necessary before you can give yourself away.

While Burtchaell makes some remarks on the wedding itself at the end of the book, the last

major issue he considers, before summing up the implausible promise that is marriage, is children.

He tackles the issues of abortion, unwanted children, and parenting by choice. For the sake of

brevity, we will link these together. Abortion from the point of view of Burtchaell arose from the

idea that it is better off to not allow a child to be born, than for a child to be born in a situation that

is not suitable. The logic seems to suggest that abortion is better than a lifetime of suffering, and a

drain on human society, and since fetuses don’t have the claim to life that developed people do,

abortion actually makes sense.

Burtchaell debunks this argument in many ways, but one of his best arguments is that it is

the children who are wanted that are more likely to become the objects of abuse. Children who are

desperately wanted often become an object of ownership that are there to satisfy parental needs,

rather than the fruit of human love. Meanwhile, children that are originally not wanted are seen as

7

a gift when they come, and contrary to popular belief become the subject of parental love more

often than not. This demonstrates that parenting by choice is not in fact a solution.

One of Burtchaell’s final arguments is that children are an essential part of marriage

because they actually require their parents to mature. He notes that husbands and wives actually

begin to change upon finding out that they are pregnant. The birth of a baby, as mentioned before,

brings another claim on a person’s life. A mother and father have to commit themselves again, and

make another pledge, as children divide time but increase love. This is not particular to the

individual family, but society as a whole. Even people that don’t have kids play a parenting role.

Almost everybody has encounters with children, and Burtchaell argues that adults need children.

Children give meaning to the lives of everybody that they come into contact with, and some

children by the nature of their disabilities require more than two parents. It is important for

Burtchaell that we see ourselves as a society of parents.

This synopsis of Burtchaell’s book, For Better, For Worse, has not been an exhaustive

treatment of the text. He packs a lot into 150, pages and it is difficult to cover all his points. What

is important to understand about this book is that the family unit, and the sacrificial love it

requires, makes the most sense when seen in light of authentic Christian faith. It is hard to argue

with Burtchaell here. Even if someone was not devoutly Christian, it would be hard to dismiss his

arguments. Christianity is about commitment, sacrificing, and pledging ourselves to others based

on faith, and so is life in a marriage and family.

Christianity means that there is no way to know what is ahead of us when we make the

commitment to follow Christ, yet regardless of what does arise, we will continue to follow. And

so, the marriage commitment is the same. It is fairly obvious that we cannot predict the future, and

so an oath of life that lays the claim, “’til death do us part” requires a blind commitment that is

open to anything. When someone enters a Christian marriage, they are literally saying that no

8

matter what comes up, I will not part from my spouse, or children aside from death. This takes

faith. This is the faith that we are to have in Christ, which was gifted to us by Christ out of his

faith in the Father.

1

Comparison Essay

Assignment: Write a three page essay that compares the discussions of creation by Helwig and Rae.

Include your evaluation of the persuasiveness of their argument.

The stories of creation are positioned at the beginning of the Bible, suggesting, perhaps,

that understanding creation is a building block for forming other beliefs about Christian faith and

life. Correctly grasping their meaning is vitally important. Murray Rae in Christian Theology and

Monika Hellwig in Understanding Catholicism offer their positions on and interpretations of the

two creation stories found in the book of Genesis. Although Rae and Hellwig approach the topic

from different denominations and use different language in their discussions, they both make

remarkably similar arguments about creation. This essay will argue that Hellwig and Rae do in fact

make the same points regarding two key aspects of the creation stories, and it will demonstrate

how Rae’s writing is more persuasive on these matters.

The first point by which to compare and contrast Hellwig and Rae is their position on how

one should interpret the stories of creation. Both authors acknowledge that it is a mistake to read

the stories literally. Hellwig states that a literal reading would make the interpreters “unaware of

the literary genre intended by the original authors of those stories.”

1

And she instead offers that the

authors are using “suggestive analogies”

2

to communicate truths about creation. Rae agrees in

saying that those who interpret these stories literally “find themselves having to deny, or having to

find some other explanation for, the vast body of evidence in favor of evolution.”

3

Although Rae

describes the literary form using different terms, as “a kind of parable”

4

that can be compared to

the parables Jesus used, he comes to the same conclusion as Hellwig: the stories are not scientific

recordings of creation; nevertheless, the stories do communicate important truths about God and

creation.

In this discussion, Rae proves to be more persuasive. Hellwig declares the authors “must

2

_________________

1

Monica K. Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 2nd ed. (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2002), 39-40.

2

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 40.

3

Murray Rae, Christian Theology: the Basics, Basics (London: Routledge, 2015), 24.

4

Rae, Christian Theology, 25.

speak in the language of poetic imagery and suggestion”

5

because they are writing about “matters

that lie beyond the boundaries of precise, appropriate and masterful language”

6

but fails to more

deeply develop her reasoning. On the other hand, to support his claim, Rae takes the time to

introduce the idea of literary genre, list the different types of genres contained in the Bible, and

illustrate his point by comparing the creation stories to the parables of Jesus. Rae concludes with a

convincing statement about how this genre can still communicate truth, “The truth revealed

through the parable of the prodigal son is not at all dependent upon our being able to locate the

farm, or trace the descendants of the family spoken of in the parable.”

7

Hellwig and Rae also agree on the need to interpret the stories of creation through the

incarnation. Hellwig states, “We understand what the creation stories mean from our experience of

Jesus.”

8

Jesus is the “very pattern of creation,”

9

the lens through which we are to read the stories.

Rae stresses that in order to recognize the intended meaning of the ‘dominion’ or ‘lordship’

humans received at creation, we need to adopt a “Christological interpretation,”

10

that is, looking

to the life of Christ to illuminate the stories’ fullest meaning. This shared viewpoint on

interpretation leads to the second point by which these authors can be compared.

Hellwig and Rae offer their interpretations of the stories’ instructions regarding how

humans are to live. In their own way, both writers agree that the purposes of life revolve around

relationship and compassion. Hellwig argues, “The love of God… is never separable from the love

of other people.”

11

Elsewhere she states that human life comes with a need for

_________________

5

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 30.

6

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 30.

7

Rae, Christian Theology, 25.

8

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 33.

9

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 34.

3

10

Rae, Christian Theology, 31.

11

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 36.

“companionship, partnership, community, [and] interpersonal relationships.”

12

Similarly, Rae

posits, “The relations in which we find ourselves… are constitutive of our identity as human

beings.”

13

Speaking about Christ’s example Rae says, “The life of Jesus is at all times a consistent

expression of his compassion for others.”

14

Hellwig uses the term ‘social’ to talk about orientation

with which Catholic doctrine calls humans to live, emphasizing at one point the “responsibility for

the world and for the affairs of human society”

15

that each person has. Rae does not use this

vocabulary, but certainly is in agreement on the purposes of relationship and compassion stating,

“Our relationships with others are not secondary to who we are.”

16

Rae’s claims are more persuasive about the purpose of relationship and compassion

because his writing clearly builds a case, whereas Hellwig’s writing interweaves her ideas

throughout without as much development. As Rae quotes the books of Psalms and 2 Corinthians,

draws upon the writings of church fathers as well as modern theologians, and incorporates reason

he builds a case for his claims about the purpose of creation being human relationships and

compassion. Although the same themes are certainly present, Hellwig’s writing primarily refers to

tradition to back her claims, and the arguments are not offered with as much support as Rae’s.

In conclusion, despite different styles, word choices, and denominational backgrounds,

Hellwig and Rae agree on the proper interpretation of the creation stories being allegorical and

Christological and the purposes for life they communicate as relational and compassionate. Both

authors articulate their claims clearly, but Rae’s more thorough explanations, clearer structure, and

use of various sources set Christian Theology apart as more persuasive writing.

_________________

12

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 31.

13

Rae, Christian Theology, 36.

14

Rae, Christian Theology, 41.

4

15

Hellwig, Understanding Catholicism, 36.

16

Rae, Christian Theology, 36.

1

Critique

Bader-Saye, Scott. “Keeping Faith in a Fearful World.” At This Point: Theological Investigations

in Church and Culture. Vol. 2 (Fall 2006). http://www.atthispoint.net/articles/keeping-

faith-in-a-fearful-world/156 (accessed February 11, 2016).

In this article, Professor Scott Bader-Saye of the Department of Theology at the University

of Scranton distills the main points of his book, Following Jesus in a Culture of Fear. He directs