Academic Writing Basics

Academic Writing Basics

Megan Robertson

KWANTLEN POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY

SURREY, BC

65;-5;:

Part I. Academic Writing Basics

1. Acknowledgements 1

2. Table Of Contents 3

3. How this Resource Works 5

4. Assessing Current Knowledge 7

5. Building Basics 11

6. Thinking About Your Assignment 17

7. Keyword Clues - Determining the

Type of Writing

21

8. Types of Academic Writing 27

9. Breaking Down an Assignment 31

10. Concept Mapping 35

11. Outlining 45

12. Developing Your Thesis Statement 53

13. Refining Your Thesis Statement 61

14. Planning Your Writing - Drafting

Paragraphs

65

15. Planning Your Writing - Quoting,

Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

67

16. Planning Your Writing -

Incorporating Evidence

75

17. Planning Your Writing - Overcoming

Obstacles

83

+256>3-,/-4-5;:

Academic Writing Basics draws on and synthesizes the

contributions of the Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Learning Centre team, including source materials, learning

aids, and workshop content created and updated by

Learning Strategists, Learning Centre Staff, and Peer

Tutors. Thanks to Karen Meijer-Kline, Mustafa

Mohammed, and Rajiv Jhangiani for their technical

assistance on this project. Kim Tomiak provided helpful

editorial suggestions.

Academic Writing Basics adopts and adapts Open

Access material from a variety of sources including:

• College of DuPage Library

• Department of Writing and Rhetoric at the

University of Mississippi

• The Excelsior College Online Writing Lab

• Mount Royal University Library

• University of California Los Angeles Library

• University of Guelph Library

• University of Laurier Library

• University of Northern British Columbia

Academic Success Centre

1

• Saylor Academy

• The Word on College Reading and Writing by

Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin,

Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear

These sources are credited where the material appears.

Material in “Types of Academic Writing” is reproduced

with permission from The University of Sydney Learning

Centre.

2 Megan Robertson

$)*3-.65;-5;:

65;-5;:

• Introduction

• How this Resource Works

• Assessing Current Knowledge

• Building Basics

• Thinking About Your Assignment

• Keyword Clues – Determining the Type of

Writing

• Types of Academic Writing

• Breaking Down an Assignment

• Concept Mapping

• Outlining

• Developing Your Thesis Statement

• Refining Your Thesis Statement

• Planning Your Writing – Drafting Paragraphs

• Planning Your Writing – Quoting, Paraphrasing,

and Summarizing

• Planning Your Writing – Incorporating Evidence

3

6>;01:"-:6<9+-'692:

@9-),15/)5,+6473-;15/)+;1=1;1-:15;01:9-:6<9+-

@6<>133*-)*3-;6

• Consider the process of academic writing;

• Determine the type of academic writing you

might be asked to complete;

• Review approaches to developing and

structuring ideas using concept mapping and

outlining;

• Work on how to develop a thesis statement or

controlling idea;

• Consider strategies for planning your writing

assignment, including:

◦ Drafting paragraphs

◦ Quoting, paraphrasing, and

summarizing

◦ Incorporating evidence, and

◦ Overcoming obstacles;

• Use key questions for revising and editing.

5

There are activities for you to do throughout this

resource. Each activity will have this banner above it:

6 Megan Robertson

::-::15/<99-5;56>3-,/-

7

If you are new to academic writing, have done some

academic writing, or are already an experienced academic

writer, there is always more to learn!

Reflecting on your current writing process can help you

decide what steps to take next.

Take the quiz below to determine if you are currently at

the beginning stages of academic writing, the intermediate

stages, or in the experienced stages.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded

from this version of the text. You can view it

online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=27#h5p-1

9

<13,15/):1+:

11

As we cover academic writing basics, you’ll see tips and

suggestions especially for beginning academic writers.

Intermediate and experienced academic writers can also

use these strategies and approaches.

Based on your current stage of academic writing,

consider how the information and examples used in this

Pressbook may be applied for your specific background

and experience:

Beginning writers may

want to closely follow

templates and resources to

learn more about

conventions and

expectations of academic

writing. This can help you

become more familiar with

the basics of academic

writing.

13

Intermediate writers

may have some knowledge

of the conventions and

expectations of academic

writing. Adapting and

extending examples used

in this workshop can help

further develop your

writing skills and your

own voice as an academic

writer.

Creatively reflecting on

the material in this

workshop can help

experienced academic

writers further refine

ideas. By experimenting

with different approaches

that complement your

existing writing process,

you can learn more about

how to best showcase your

research and discussion.

14 Megan Robertson

15

$015215/*6<;(6<9::1/54-5;

17

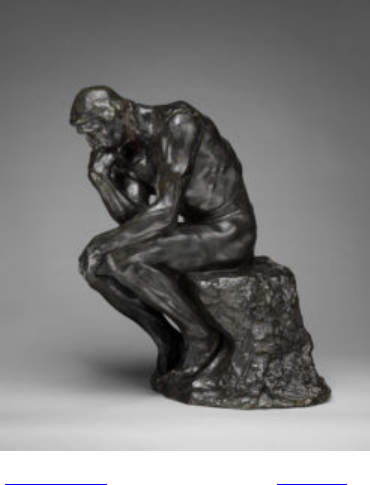

“The Thinker” by Auguste Rodin CC0 1.0

When you receive your writing assignment from your

instructor, it’s important to stop and think. What are the

requirements? What is the purpose of this assignment?

What is your instructor asking you to write? Who are you

writing for?

Before you begin to write any part of an assignment,

think about the requirements and how you plan to meet

those requirements. It’s easy to jump into an assignment

without stopping to think about and analyze the assignment

requirements.

What does it mean to think about and analyze

assignment requirements?

It means that you’re considering the purpose of the

assignment, the audience for the assignment, the voice you

19

might want to use when you write, and how you will

approach the assignment effectively overall.

With each writing assignment, you’re being presented

with a particular situation for writing. Learning about

assignment requirements and expectations can help you

learn to make good decisions about your writing.

Every writing assignment has different expectations.

There is no such thing as right, when it comes to writing;

instead, try to think about good writing as being writing

that is effective in that particular situation.

Adapted from “Thinking about Your Assignment” by

Excelsior Online Writing Lab CC BY 4.0

20 Megan Robertson

-@>69,3<-:-;-941515/;0-$@7-

6.'91;15/

21

When you receive an assignment from an instructor, paying

close attention to the assignment description and

expectations can help you determine what will be most

effective for your writing.

Looking for and highlighting keywords in your

assignment can help you know what your instructor

expects. Try it out! Match the keywords below with their

definitions:

23

An interactive H5P element has been excluded

from this version of the text. You can view it

online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=36#h5p-4

1

These are just some of the keywords that you might see

in an assignment. Review the KPU Learning Aid “Terms

that may be used in essays or examinations” to see more

Beginning, intermediate, or experienced as an academic

writer, if you are uncertain about assignment requirements

– ask your instructor! You can also visit the KPU Learning

Centres for help with determining what type of writing you

are being asked to do.

In the next section, we’ll take a closer look at

four of the common types of academic writing that

you might encounter and the keywords that are

associated with each type of writing.

1.

2

2. [1]

24 Megan Robertson

If you are a beginning

academic writer, in your first

semester of university studies,

you will likely start with some

descriptive writing.

By the end of your first

semester, you may be expected

to include analysis, persuasion,

and critique in your writing.

Most of the academic writing you will do as a university

student will include a combination of these different types

of writing.

If

you

are an

intermediate or experienced

academic writer, you may already be familiar with these

type of writing.

Below, we’ll look more closely at the four different types

of writing (descriptive, analytical, persuasive, and critical)

and consider strategies for developing ideas.

Click on the titles to expand the sections.

28 Megan Robertson

An interactive H5P element has been excluded

from this version of the text. You can view it

online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=59#h5p-2

1

1. Description and discussion of types of writing reproduced, with permission,

from "Types of Academic Writing" by University of Sydney Learning

Centre https://sydney.edu.au/students/writing/types-of-academic-

writing.html

Academic Writing Basics 29

9-)215/6>5)5::1/54-5;

Once you know about the expectations related to the type

of writing that you are required to do, you can make a plan

to gather information and develop your ideas.

Let’s look at an example, we’ll come back to this

example throughout the different sections of this

Pressbook…

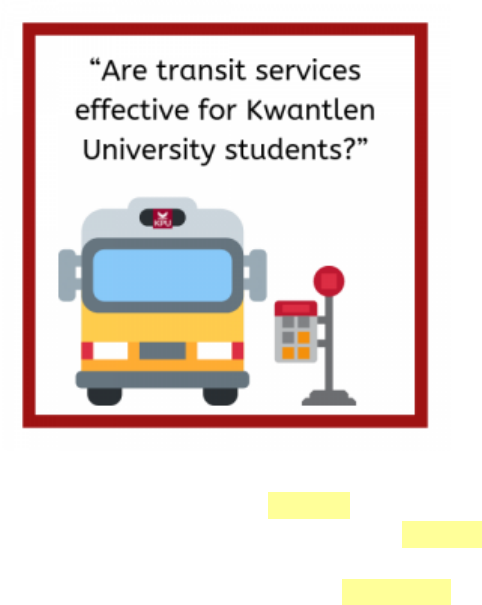

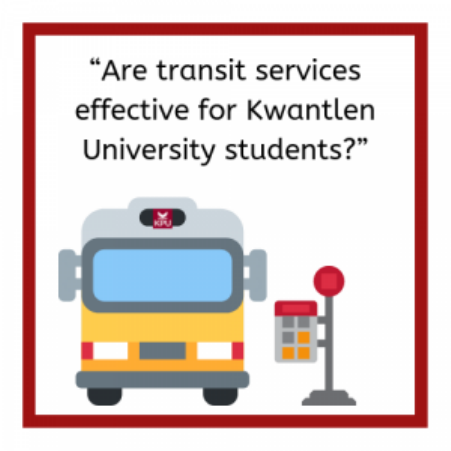

An instructor in a first-year communication course asks

students to complete the following assignment:

Write a 1,500 word persuasive essay that responds to

the question: “Are transit services effective for Kwantlen

University students?” Include your own perspective in

your analysis and draw on two academic sources.

31

In my assignment, I’ll need to describe transit services.

Once I have my description, I can include some analysis of

those services, based on my own perspective and sources

that I’ll need to identify. Because this is a persuasive essay,

I want to make sure that I’m presenting a clear argument.

I can already see that I’ll be using three types of academic

writing in this one assignment!

As I work on my assignment, it is important that I keep

checking back with the assignment instructions; I want to

make sure that I’m staying on topic and responding to the

question.

Now that I have an understanding of the type of

assignment that I’m working on, I can begin to develop

ideas, gather information, and organize what I want to

say. We’ll look more closely at brainstorming and concept

mapping, next.

32 Megan Robertson

What are Academic Sources?

Academic Sources:

• Are published in a peer-reviewed

journal or by a reputable publisher

• Use academic or scholarly language

• Include a reference list

• Include the author’s credentials

• Report the results of some kind of

research or study

From “General Education: Scholarly and Popular

Resources” by Mount Royal University Library CC

BY-NC-SA 4.0

Academic Writing Basics 33

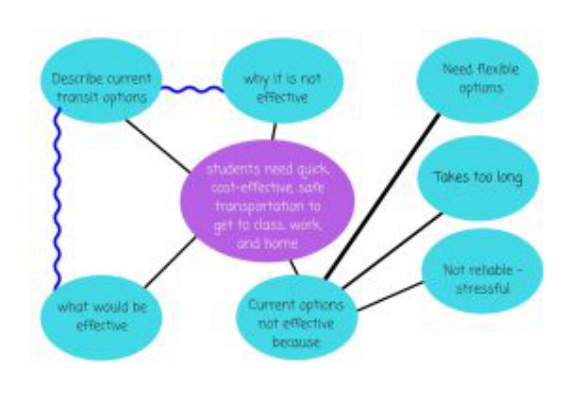

65+-7;)7715/

Creating a concept map is a way of organizing your

brainstorming around key concepts.

This video from the University of Guelph offers a brief and

helpful overview of concept mapping:

1

One or more interactive elements has been

excluded from this version of the text. You can

view them online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=44#oembed-1

Ready to get started with a concept map? This KPU

learning aid can also help guide you through the process.

Let’s use our example where an instructor has given us

the assignment: Write a 1,500 word persuasive essay that

responds to the question: “Are transit services effective

for Kwantlen University students?” Include your own

1.

2

2. [1]

35

perspective in your analysis and draw on two primary and

two academic sources.

We’ll follow the seven steps of concept mapping

outlined in the video above and I’ll include some examples.

If you have your own assignment that you are

currently working on, use the steps below to make

your own concept map for your assignment.

36 Megan Robertson

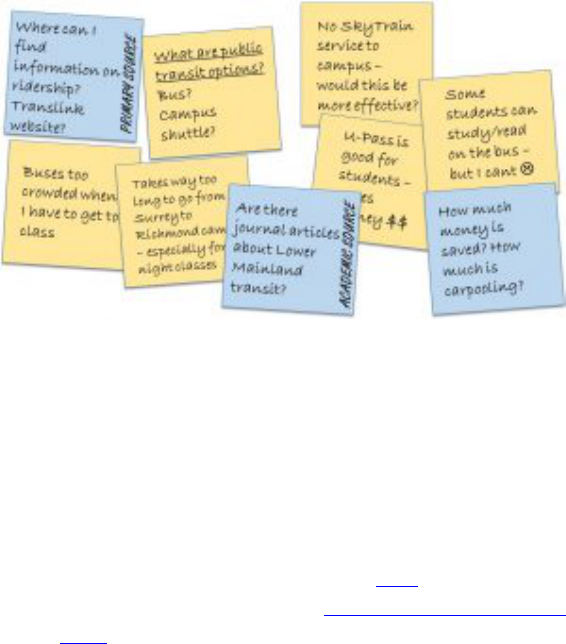

#;-75-

• Identify the main topic

• Brainstorm everything you know about the topic

• Use relevant content from course, lectures,

textbooks, and course material

Sticky notes can be a great way of jotting down ideas

– you can move the notes around as you begin to identify

similarities and differences. You can also ask questions and

include reminders of work that that you need to do. See the

example below of some sticky notes I might use to start my

assignment:

I’ll add more sticky notes with key questions that

relate back to the assignment – I’ll need to find

primary and academic sources:

Academic Writing Basics 37

I can use these questions as I begin my research

process and identify the primary and academic

sources I need to support the argument that I will

make.

To find out more about the research process, visit

any of KPU’s libraries to get help from a librarian, or

review one of the helpful guides here to get started.

This video, included in KPU Library’s Research

Help page, provides a good overview of working

with an assignment to make sure that you develop a

response that is specific and well-supported:

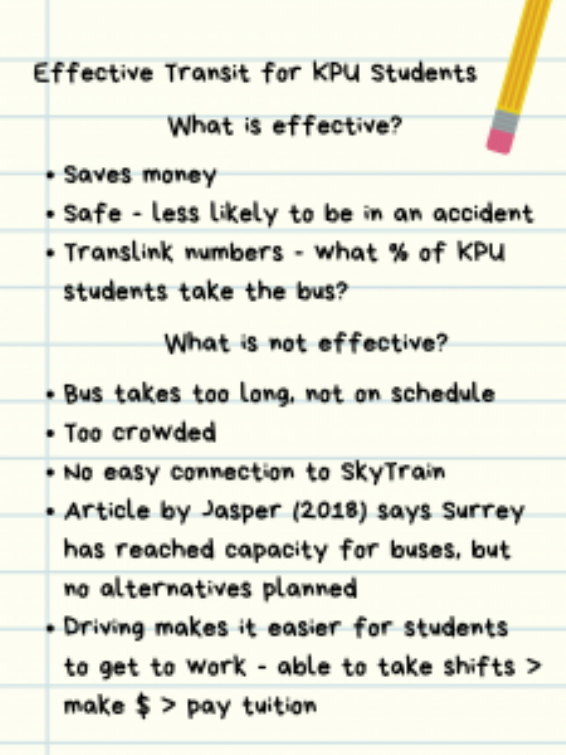

#;-7$>6:

• Organize information into main points

After noting down what I know about my topic and

identifying key questions that I’ll need to research

everything, I can focus on a few things that will be

38 Megan Robertson

important to describe and analyze in my essay. I’ve made a

list of some that I can use:

Based on what I’ve done so far, I’m setting up a

descriptive comparison of transit options for KPU students,

but will emphasize that current transit options are not

Academic Writing Basics 39

effective. I want to look for further connections between

ideas and see how I can shape my argument.

#;-7$09--:

• Start creating map

• Begin with main points

• Branch out to supporting details

Give it a try! Based on your experience of public transit

and the ideas that I’ve outlined so far, how might you start

to create a concept map? You can use a piece of paper, or

concept mapping software, to make note of ideas and start

to connect them.

#;-76<9:

• Review map and look for more connections

• Use arrows, symbols, and colours, to show

relationships between ideas

I start to build layers of connections and relationships in

my map:

40 Megan Robertson

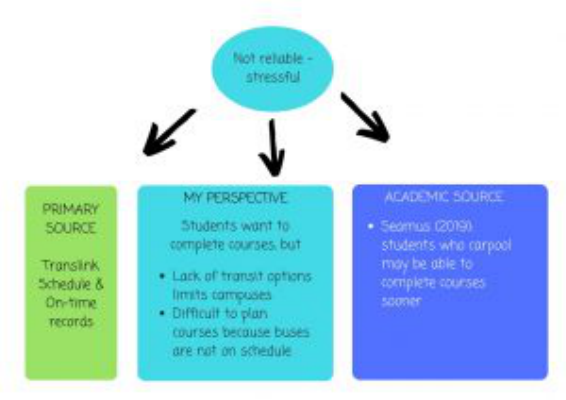

#;-71=-:

• Include details

This is where I can provide more information about each

point – below, I’ve taken one of the points and added to it:

Academic Writing Basics 41

#;-7#1?:

• Analyze and improve map by asking questions

• How do ideas fit together?

• Have all necessary connections been made?

This is where I can step back and review my map and

keep the purpose of my assignment in mind. This is also

a good time to follow up on questions that I might have –

I can talk through my ideas with a classmate or visit my

instructor as I continue to develop and refine my ideas.

#;-7#-=-5:

• Update concept map as you learn more

• Ask key questions about connections between

42 Megan Robertson

ideas

I’ll keep my map with me as I meet with my instructor to

discuss my ideas and when I visit the library to locate any

academic resources that I might need; this way, I can keep

everything together.

1. “How to Create a Concept Map” by University

of Guelph Library CC BY-NC-SA 4.0↵

Academic Writing Basics 43

<;31515/

Once you have your concepts and know how you are going

to connect your concepts, you can start to shape your essay

by working on an outline. An outline can help structure

your writing – but it is flexible! Imagine that your outline is

your travel plan for what you want to do on your vacation

– you know which sights you want to see, which pictures

you want to take, and where you want to go. Once you

know this, you can then decide how you’re going to do

these things: what do you want to visit first? How will

you travel between destinations? How long will you stay in

each place?

45

“My work space” by oxana v on Unsplash

For your writing journey, an outline can help you answer

similar questions: which concept do you want to discuss

first? How will you travel between different concepts?

How much will you write about each concept?

Your outline helps you plan and structure what you want

to say and in what order you will say it. As your ideas

develop, you may adjust your outline so that it better fits

with the concepts you want to connect and the evidence

you will use to support your ideas.

You can follow this KPU learning aid to learn more

about structuring your outline.

46 Megan Robertson

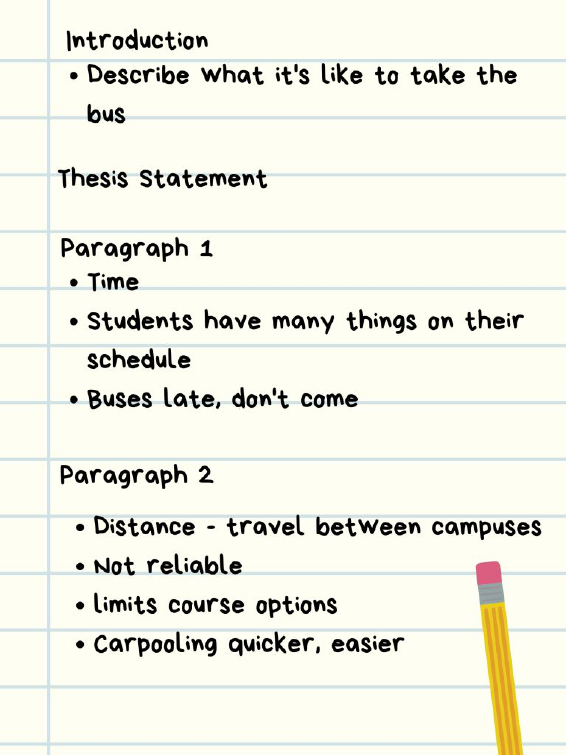

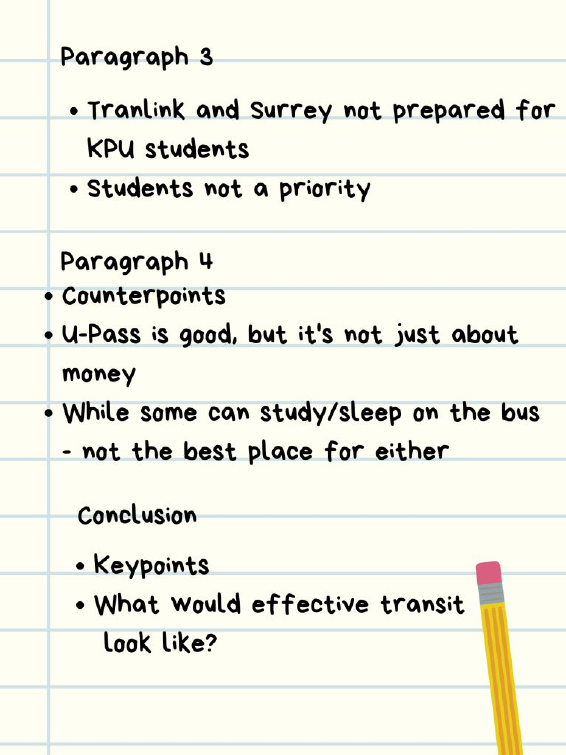

Using our example writing assignment, I can get started

on my outline.

I’ll group ideas and concepts into paragraphs:

Academic Writing Basics 47

48 Megan Robertson

Right now, I haven’t written my thesis statement, but

that will be my next step.

If you are an intermediate or an experienced academic

writer, you might want to try creative graphic approaches

to outlining.

Academic Writing Basics 49

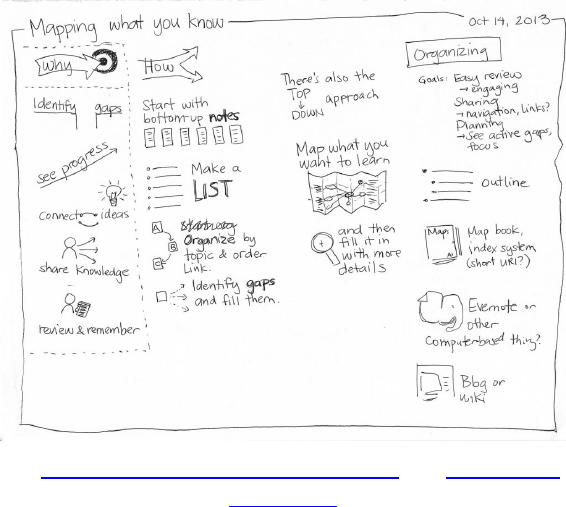

Below you can see an example of using text and drawing

to organize key ideas and assess options when putting

together a project.

50 Megan Robertson

-=-36715/(6<9$0-:1:#;);-4-5;

After you have started to develop your ideas and mapped

out the main concepts that you will cover in your

assignment, it can now be a good time to consider what will

be your thesis statement.

Remember that your thesis statement can change as you

continue to develop your ideas – using an outline can help

you keep checking on the connection between your body

paragraphs and your thesis statement.

Sometimes, thinking of a question can help you focus

your ideas and make connections.

In this video

1

, you can see how a question can be used

to structure and develop a thesis statement (Note, video

has no narration; a transcript of the text used on screen is

available below):

One or more interactive elements has been

excluded from this version of the text. You can

view them online here:

1. "How to Write a Thesis for Beginners" CC BY 4.0

53

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=47#oembed-1

The three steps outlined in the video:

• Creating a question about your topic

• Finding reasons, and

• Putting it all together

are a good place to start if you are a beginner academic

writer.

Another strategy to developing a thesis statement is to

use the template suggested in this KPU Learning Aid on

“Thesis Statement Design:”

Using the KPU Learning Aid, we can return to our

example:

54 Megan Robertson

Here is the suggested template:

Academic Writing Basics 55

By beginning to to organize my ideas about effective

transit and KPU students, I can say:

56 Megan Robertson

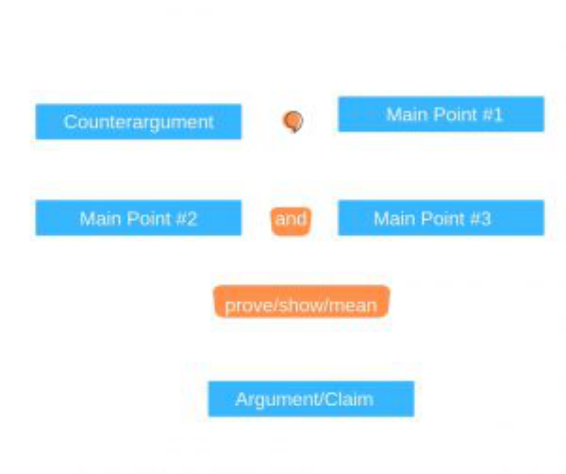

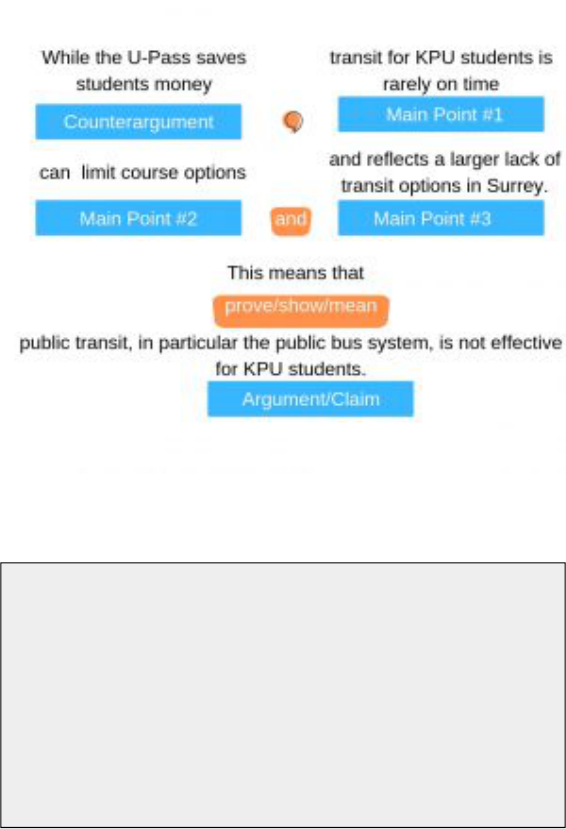

Right now, my thesis is two sentences:

While the U-Pass saves students money, transit

for KPU students is rarely on time, can limit course

options, and reflects a larger lack of transit options

in Surrey. This means that public transit, in

particular the public bus system, is not effective for

KPU students.

My thesis may change as I continue to write and revise

my essay. In the next chapter, we’ll look at more questions

Academic Writing Basics 57

suggestions you can use to further refine your thesis

statement.

Transcript for Text from “How to Write a Thesis for

Beginners”

Writing a Thesis Statement

Step 1 (creating a question about your topic)

What is your topic?

Superman

Form a question

Why is Superman so cool?

Step 2 (finding reasons)

What are some of the reasons that Superman is

cool?

(Try to think of at least 3 reasons)

Superman can fly!

He saves people from danger

Superman is really strong

That’s why he is Superman!

Step 3 (putting it all together)

We need to take the information from step 1 and

2 and combine it Make sure to answer your question

Why is Superman so cool?

Superman is so cool because

58 Megan Robertson

(part 1)

he is strong, helps people in danger, and he can

fly.

(part 2)

Remember your thesis is the road map for writing

your paper.

Make sure you write about what your thesis says.

Whether you are writing about Superman, China, or

Australia.

Academic Writing Basics 59

"-C515/(6<9$0-:1:#;);-4-5;

61

As you develop experience and confidence as a writer, you

can consider more steps to improve your thesis statement,

like those ones discussed in the University of Laurier

Library video

1

:

One or more interactive elements has been

excluded from this version of the text. You can

view them online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=204#oembed-1

If you are able to:

• Make an argument

• Answer ‘so what?’

• Be specific

• Have only one idea

• Make it supportable

You can make improvements in your thesis statement.

See if you can identify strong thesis statements:

1. "Improving Your Thesis Statement" by Laurier Library CC BY 4.0

63

3)5515/(6<9'91;15/9).;15/

)9)/9)70:

Once you have an outline and a thesis statement, you can

work on the paragraphs in your assignment and start

writing your first draft.

Following the MEAL plan can help you structure your

paragraphs:

Click on the sections below to find out more about the

MEAL plan for paragraph drafting:

65

3)5515/(6<9'91;15/!<6;15/

)9)709):15/)5,#<44)91A15/

An important part academic writing is incorporating

evidence. To do this, you will need to know the basics of

quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing.

Making sure that you are using evidence properly,

through quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing, will

67

ensure that you are giving necessary credit for other

peoples’ words and ideas and will help you avoid

plagiarism.

The table

1

below describes three different ways of using

evidence:

Quoting

Using the author’s exact words. Always cite it

and use “quotation marks.”

Paraphrasing

Restating, in your own words, the author’s

words or ideas without altering the meaning

or providing interpretation. Paraphrases are

about the same length as the original. Always

cite it.

Summarizing

Condensing the author’s words or ideas

without altering the meaning or providing

interpretation—you use your own words for

this. Basically, presenting the original

information in a nutshell. Always cite it.

..-+;1=-3@8<6;15/7)9)709):15/)5,:<44)91A15/

)3>)@:15+3<,-:+1;);165

We’ll review some examples of how you can effectively

incorporate evidence to support your ideas in the next

section. Before we get there, make sure that you are

familiar with the citation style and reference style that you

1. "Quoting, Summarizing, and Paraphrasing in a Nutshell" by University of

California Los Angeles Library CC BY 4.0

68 Megan Robertson

are using for your assignment – these can be different for

different courses and assignments.

The KPU Library has guides to help you with make sure

that you are citing your work correctly, according to the

style that your instructor wants you to use. Visit their page

here.

If you have questions about how you should be citing

evidence, ask your instructor or check with one of the KPU

librarians.

Complete the KPU Plagiarism Awareness

Tutorial to learn more about academic integrity and

earn your Moodle badge.

967-93@#<44)91A15/)5, )9)709):15/

2

When you summarize, you should write in your own words

and the result should be substantially shorter than the

original text. In addition, the sentence structure should be

your original format. In other words, you should not

take a sentence and replace core words with synonyms

(different words with the same meaning).

You should also use your own words when you

paraphrase. Paraphrasing should also involve your own

sentence structure. However, paraphrasing might be as

long or even longer than the original text. When you

paraphrase, you should include, in your words, all the ideas

2. Material in this section is reproduced and adapted from "Making Ethical and

Effective Choices" by Saylor CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Academic Writing Basics 69

from the original text in the same order as in the original

text. You should not insert any of your ideas.

Both summaries and paraphrases should maintain the

original author’s intent and perspective. Taking details out

of context to suit your purposes is not ethical since it does

not honor the original author’s ideas.

Review the examples in the table below to see the

difference between quoting, paraphrasing, summarizing,

and plagiarizing.

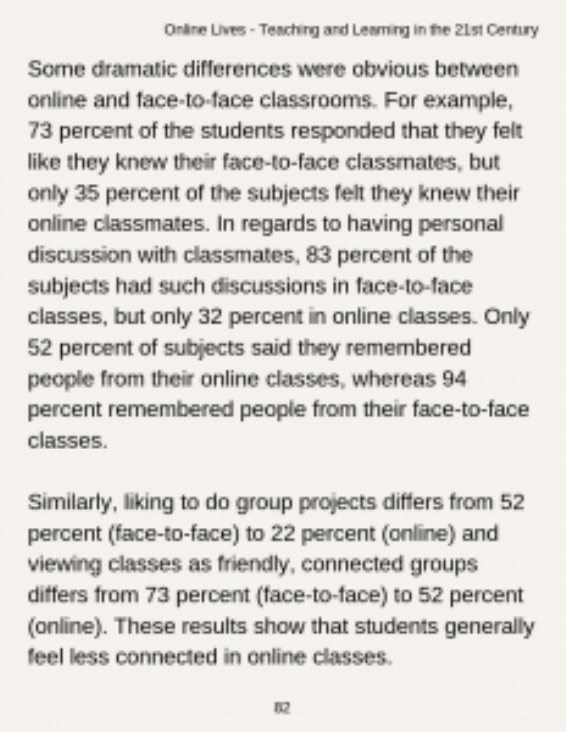

Here is a page from a book written by Maelle Jasper:

70 Megan Robertson

Academic Writing Basics 71

Quoted Text

The study showed that personal discussions

are much more likely to take place in

face-to-face classes than in online classes

since “83 percent of the subjects had such

discussions in face-to-face classes, but only 32

percent in online classes” (Jasper, 2016, p. 82).

Paraphrased

Text

Study results (Jasper, 2016, p. 82) show a clear

difference between online and face-to-face

classrooms. About twice as many students

indicated they knew their classmates in

face-to-face classes than in online classes.

Students in face-to-face classes were about

two-and-a-half times more likely to have

discussions with classmates than were students

in online classes. Students in face-to-face

classes were about twice as likely to remember

classmates as were students in online classes.

Students in face-to-face classes viewed group

projects as positive about two-and-a-half times

more often than did students in online classes.

Students in face-to-face classes saw class as a

friendly place 73 percent of the time compared

to 52 percent for online classes. Summing up

these results, it is clear that students feel more

connected in face-to-face classes than in

online classes.

Summarized

Text

Students report a more personal connection to

students in face-to-face classes than in online

classes (Jasper, 2016, p.82).

I

n

t

h

e

e

x

a

m

p

l

e

o

f

p

l

a

g

i

a

r

i

z

e

d

t

e

x

t

,

s

o

72 Megan Robertson

Plagiarized

Text

Some major differences were clear between

Internet and in-person classrooms. For

example, 73 percent of the study participants

felt they were acquainted with their in-person

classmates, but only 35 percent of the

participants indicated they knew their distance

classmates.

me of the words from the original text are replaced with

synonyms (different words with the same meaning).

Below you can see how the words that are underlined in

the original text have been replaced in the plagiarized text

with synonyms (highlighted in yellow).

Original

Text

Some dramatic differences were obvious

between online and face-to-face classrooms. For

example, 73 percent of students responded that

they felt like they knew their face-to-face

classmates, but only 35 percent of the subjects

said they remembered people from their online

classes.

Plagiarized

Text

Some major differences were clear between

Internet and in-person classrooms. For example,

73 percent of the study participants felt they

were acquainted with their in-person classmates,

but only 35 percent of the participants indicated

they knew their distance classmates.

The only noticeable difference between the original text

and the plagiarized text are the synonyms. This form of

plagiarism is also known as “patch writing.” The original

Academic Writing Basics 73

and the plagiarized text are identical, except for “patches”

where synonyms have been used.

Patch writing

3

You copy a short passage from an article you

found. You change a couple of words, so that it’s

different from the original. You carefully cite the

source. It is still PLAGIARISM because even

though you have acknowledged the source of the

ideas with a citation, your new passage is too close

to the original text. This form of plagiarism is called

patch writing. In patch writing, the writer may

delete a few words, change the order, substitute

synonyms and even change the grammatical

structure, but the reliance on the original text is still

visible when the two are compared.

3. "Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing & Patchwriting Quotations" by College of

DuPage Library CC BY 4.0

74 Megan Robertson

3)5515/(6<9'91;15/5+69769);15/

=1,-5+-

In the previous section, we reviewed quoting,

paraphrasing, and summarizing. Academic writing uses

quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing, together with

your own word and ideas to communicate your

perspectives.

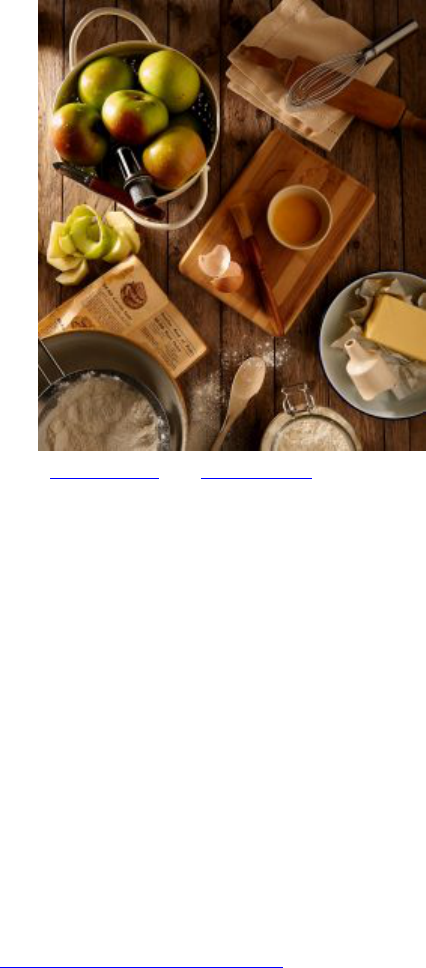

One way to think about incorporating evidence is to

imagine that the person reading your writing visits a bakery

to pick up a pie. Your reader is expecting something like

this:

75

“Pie on wood slab” by Rebecca Matthews

on Unsplash

As a writer, your reader expects you to combine and

incorporate all of the ingredients in the proper order. If your

reader is expecting a well-made apple pie, but you don’t

combine the ingredients, like the picture below, the reader

might not be sure what to do with them.

76 Megan Robertson

“Baking a Pie” by Andy Chilton on Unsplash

Even if you have good ingredients, you need to blend

them together! When you are working on a writing

assignment, even if you identify good evidence to support

your thesis, you need to organize and incorporate that

evidence and supporting material with your own ideas and

your own writing.

So, how can evidence be incorporated with your own

ideas and your own writing?

There are three basic elements to keep in mind when

incorporating evidence:

1

Effectively using evidence is not just about properly

documenting your evidence, but also where and how you

1. From "Integrating Evidence into Your Writing" by University of Northern

British Columbia Academic Success Centre

Academic Writing Basics 77

incorporate evidence into your writing, and how you

explain its significance to your argument.

To effectively show the reader how evidence supports

your claims, use a well-organized

paragraph structure in combination with language signals.

Language signals such as “for example,” “therefore,” and

“in contrast,” for instance, help make connections and

transitions between ideas more clear to the reader.

Use this basic pattern as a guide to incorporate evidence

into your paragraph:

#;);-@6<9+3)14)5,,-C5-)5@;-94:;0);4)@

56;*-256>5;6@6<99-),-9

96=1,--=1,-5+-;0);:<7769;:@6<9+3)14

644-5;6506>;0--=1,-5+-:<7769;:@6<9

+3)14

The third element is where you clearly explain the

connection between your claim and the evidence to the

reader. Do not assume the reader automatically understands

the connections between your ideas—you must explain

them!

Using our example of a writing assignment that asks us

to discuss effective transit options for KPU students, we

can now do the following:

78 Megan Robertson

#;);-@6<9+3)14)5,,-C5-)5@;-94:;0);4)@56;

*-256>5;6@6<99-),-9

While Surrey has one of the largest populations in Metro

Vancouver, the “federation of 21 municipalities, one

Electoral Area and one Treaty First Nation” in southwest

British Columbia (Metro Vancouver, 2019, para. 1), it is

under served by public transit. Surrey’s current Skytrain

service, in particular, does not support the transportation

needs of Kwantlen students or the city’s residents.

• In the paragraph above we have:

Academic Writing Basics 79

◦ Defined a key term – “Metro

Vancouver”

◦ Incorporated a quotation from a

source into our sentences

96=1,--=1,-5+-;0);:<7769;:@6<9+3)14

Skytrain service extended to Surrey following Vancouver’s

hosting of Expo ’86 and by 1994, the ‘Expo Line’ included

20 stations stretching from Downtown Vancouver to

Surrey’s King George Station – one of fours Skytrain

stations in Surrey (Translink, n.d.). The City of Surrey

website notes that the city “has had an average annual

growth rate of 2% over the last 10 years” (City of Surrey,

n.d.). By 2021, an estimated 600,000 people will call

Surrey, but Skytrain service is not scheduled to expand.

• In the paragraph above, we have:

◦ Used specific evidence related to our

claim

◦ Incorporated evidence into our

sentences using quotation and

paraphrase

644-5;6506>;0--=1,-5+-:<7769;:@6<9+3)14

The lack of Skytrain stations in Surrey, and with no current

plans to build more, means that both Surrey residents and

80 Megan Robertson

Kwantlen students will struggle with reliable

transportation. Because of this growing population base,

more and more Surrey residents will make use of transit.

Regardless of where students attending Kwantlen’s Surrey

campus live, this growing population will create more

overcrowding on existing transit lines.

• In the paragraph above, we have:

◦ Explained why evidence matters – see

where we have used “means” and

“because”

Academic Writing Basics 81

3)5515/(6<9'91;15/=-9+6415/

*:;)+3-:

83

When you are trying to write your first draft, it can be

challenging to get started when facing a blank page!

“MacBook Pro near white open book” by Nick Morrison

on Unsplash

#6>0);+)5@6<,6

Just write. You already have at least one idea. Start there.

What do you want to say about it? What connections can

you make with it? If you have a working thesis, what points

might you make that support that thesis?

Review and update your outline. Write your topic or

thesis down and then jot down what points you might make

that will flesh out that topic or support that thesis. These

85

don’t have to be detailed. In fact, they don’t even have to

be complete sentences (yet)!

1

Create Smaller Tasks and Short-Term Goals. Your

assignment might seem too large, and maybe the due date

is weeks away. These factors can contribute to feelings of

being overwhelmed or with the tendency to procrastinate.

But the remedy is simple and will help you keep writing

something each week toward your deadline and toward the

finished product: divide larger writing tasks into smaller,

more manageable tasks and set intermediate deadlines.

Collaborate. Talk to your friends or family, or to a peer

tutor in The Learning Centre, about your ideas for your

essay. Sometimes talking about your ideas is the best way

to flesh them out and get your ideas flowing. Write down

notes during or just after your conversation. Classmates are

a great resource because they’re studying the same subjects

as you, and they’re working on the same assignments. Talk

to them often, and form study groups. Ask people to look

at your ideas or writing and to give you feedback. Set goals

and hold each other accountable for meeting deadlines (a

little friendly competition can be motivating!).

Talk to other potential readers. Ask them what they

would expect from this type of writing. Meet with a tutor in

The Learning Centre. Be sure to come to the appointment

prepared with a copy of the assignment and a clear idea of

what you want to work on.

2

Try to start writing well in advance of your deadline so

1. "Writing the First Draft" in The Word on College Reading and Writing by

Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole

Rosevear CC BY-NC 4.0

2. Adapted from "Overcoming Writing Anxiety and Writer’s Block"in The Word

on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique

Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear CC BY-NC 4.0

86 Megan Robertson

"-=1:15/(6<9'91;15/

Once you’ve worked on your draft, you need to revise and

edit your work. Revising will help you check if you’ve

responded to the assignment instructions and clearly

communicated your ideas. Revising will also help you will

help you correct grammatical, punctuation, and

presentation issues. When you are revising, try moving

through three different stages:

• Checking in on the Big Picture

• The Mid-view Review

• Editing Up Close

We’ll look first at Checking in on the Big Picture…

"-=1:15/#;)/-B0-+215/1565;0-1/ 1+;<9-

89

“Seeking Adventure” by Jasper van der Meij on Unsplash

When you first begin revising, you should focus on the

big picture. The following questions

1

can help guide you

with this:

• Do you have a clear thesis? Do you know what

idea or perspective you want your reader to

understand upon reading your essay?

• Is your essay well organized?

• Is each paragraph a building block in your

essay: does each explain or support your thesis?

• Does it need a different shape? Do parts need

to be moved?

• Do you fully explain and illustrate the main

ideas of your paper?

• Does your introduction grab the reader’s

1. Revising Stage 1 by Excelsior Online Writing Lab CC BY 4.0

90 Megan Robertson

interest?

• Does your conclusion leave the reader

understanding your point of view?

• Are you saying in your essay what you want to

say?

• What is the strength of your paper? What is

its weakness?

"-=1:15/#;)/-B$0-1,&1->"-=1->

“The south of Mexico” by Mitch Lensink on Unsplash

The second stage of revising requires that you look at

Academic Writing Basics 91

your content closely at the paragraph level. It’s now time

to examine each paragraph, on its own, to see where you

might need to revise. The following questions

2

will guide

you through the mid-view revision stage:

• Does each paragraph contain solid, specific

information, vivid description, or

examples that illustrate the point you are

making in the paragraph?

• Are there are other facts, quotations, examples,

or descriptions to add that can more clearly

illustrate or provide evidence for the points you

are making?

• Are there sentences, words, descriptions

or information that you can delete because

they don’t add to the points you are making or

may confuse the reader?

• Are the paragraphs in the right order?

• Are your paragraphs overly long? Does each

paragraph explore one main idea?

• Do you use clear transitions so the reader can

follow your thinking?

• Are any paragraphs or parts of

paragraphs repetitive and need to be deleted

Take a look at the paragraph

3

below and click the hot

spots to see suggestions for revision:

2. Revising Stage 2 by Excelsior Online Writing Lab CC-BY-4.0

3. "Revising Paragraphs" in Writing Skills Lab by Department of Writing and

Rhetoric at the University of Mississippi

92 Megan Robertson

An interactive H5P element has been excluded

from this version of the text. You can view it

online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=116#h5p-10

Practice: Revising Paragraphs

Review the paragraph

4

below and select the most

important revision that Sophie, the student writer, should

focus on in her revisions:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded

from this version of the text. You can view it

online here:

https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/

academicwritingbasics/?p=116#h5p-8

4. "Revising Paragraphs" in Writing Skills Lab by Department of Writing and

Rhetoric at the University of Mississippi CC BY 4.0

Academic Writing Basics 93

"-=1:15/#;)/-B,1;15/%736:-

Photo by Andrew Pons on Unsplash

Once you have completed your revision and feel

confident in your content, it’s time to begin the editing

stage of your revision and editing process. The following

questions

5

will guide you through your editing:

• Are there any grammar errors, i.e. have you

been consistent in your use of tense, do your

pronouns agree?

• Have you accurately and effectively

used punctuation?

5. Revising Stage 3 by Excelsior Online Writing Lab CC BY-4.0

94 Megan Robertson

• Do you rely on strong verbs and nouns and

maintain a good balance with adjectives and

adverbs, using them to enhance descriptions but

ensuring clear sentences?

• Are your words as accurate as possible?

• Do you define any technical or unusual

terms you use?

• Are there extra words or clichés in your

sentences that you can delete?

• Do you vary your sentence structure?

• Have you accurately presented facts; have you

copied quotations precisely?

• If you’re writing an academic essay, have you

tried to be objective in your evidence and tone?

• If writing a personal essay, is the narrative

voice lively and interesting?

• Have you spellchecked your paper?

• If you used sources, have you consistently

documented all of the sources’ ideas and

information using a standard documentation

style?

Academic Writing Basics 95

"-=1->)5,-?;#;-7:

5;01:9-:6<9+-@6<0)=-0),;0-67769;<51;@;6

• consider the process of academic writing;

• determine the type of academic writing you

might be asked to complete;

• review approaches to developing and structuring

ideas using concept mapping and outlining;

• work on how to develop a thesis statement or

controlling idea;

• consider strategies for planning your writing

assignment, including:

◦ drafting paragraphs

◦ quoting, paraphrasing, and

summarizing

◦ incorporating evidence, and

◦ overcoming obstacles;

• use key questions for revising and editing.

:@6<>69265@6<9>91;15/)::1/54-5;:;0- %

97